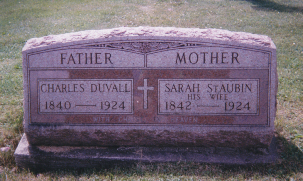

Welcome to the Duval family history page! This site is devoted to Charles and Sarah

(St. Aubin) Duval, who came to Wisconsin from Canada in 1873, and to their eight

children, thirty-

- Our first Duval ancestor to come to Canada, Charles’s great-

great- great grandfather, was a baker who arrived in Montréal shortly after 1700. He came from the town of Tonnerre, in Burgundy, about 120 miles southeast of Paris. The family name did not finally become Duval until emigration to the United States in 1873. Before then, it was Thuot (pronounced TYOO- et). - Our first St. Aubin ancestor to come to Canada, Sarah’s great-

great- great- great grandfather, arrived in Montréal as a teenager in about 1665 and was initially employed as a servant by the king’s attorney there. He came from Dieppe, in Normandy, on the north coast of France. - For the next two centuries, the Duval and St. Aubin families lived in Montréal and in the small farming communities to the south of the city.

- There are 745 documented ancestors in our family tree, and all but four were French.

The exceptions were one Spaniard, one Swiss, one Dutchman, and one African. There

were no Native American (Indian) ancestors at all. In the entire family tree, extending

more than 400 years, there were only two out-

of- wedlock births. - Of our 745 ancestors, 185 were immigrants to Canada. They were especially prominent among the founding families of Montréal, and they were nearly all peasants and laborers, although some acquired artisanal skills. There were no noble lineages, merchants, or significant government officials among them.

- Our most famous ancestors were Louis Hébert and his wife Marie Rollet, considered to be the first French family to settle in Canada, in 1617.

- We’re related to Angelina Jolie, Madonna, Celine Dion, Alec Baldwin, Jim Carrey,

Hillary Clinton, and to virtually everyone else who has French-

Canadian ancestors in his family tree. We’re also related to Saint André of Canada, canonized by the pope in 2010.

If you’d like to know more, read on . . .

OUR HISTORY IN CANADA

FRANCE AND THE FOUNDING OF CANADA

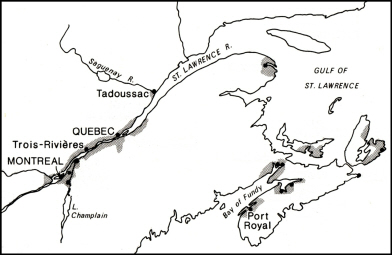

European settlement of North America began in earnest four centuries ago. The Puritans established themselves in New England, the Dutch founded New Netherland on the Hudson River, English cavaliers laid out tobacco plantations in Virginia, the Quakers began the colony that would become Pennsylvania, and the French sent settlers to Québec and Montréal on the St. Lawrence River.

American schoolchildren are familiar with the narratives of the early settlements that became the United States. Many of the colonists sought to practice their religious beliefs without interference, especially the Puritans and the Quakers. Many of them sought economic opportunity as they fled their crowded homelands and claimed the abundant farmland of the New World. They developed agriculture and industry that both served their own needs and yielded exports to Europe and the Caribbean. And they steadily pushed the Indian peoples westward, often in bloody conflict, as they expanded the frontier.

The narrative of the French in Canada is quite different. No one came in search of

religious freedom, because only Catholics were allowed to settle. Few came for economic

opportunity, because the French government strictly controlled land holding and insisted

that the colonists trade only with France and not engage in manufacturing. From the

start agriculture was difficult because of the short growing season and harsh winters.

The trade in fur, of beavers and other forest animals, was lucrative but was limited

to a small class of merchants. And while periods of conflict with the Indians occurred,

cooperation with them was the norm, given the small numbers of French settlers in

Canada and the importance of the Indians in the fur trade.

The narrative of the French in Canada is quite different. No one came in search of

religious freedom, because only Catholics were allowed to settle. Few came for economic

opportunity, because the French government strictly controlled land holding and insisted

that the colonists trade only with France and not engage in manufacturing. From the

start agriculture was difficult because of the short growing season and harsh winters.

The trade in fur, of beavers and other forest animals, was lucrative but was limited

to a small class of merchants. And while periods of conflict with the Indians occurred,

cooperation with them was the norm, given the small numbers of French settlers in

Canada and the importance of the Indians in the fur trade.

The French were drawn to the New World by codfish and beaver pelts, but if this had

been the whole story, they would never have founded settlements in Canada, because

neither commodity required a permanent presence on land. The fishing boats came seasonally

and then returned to France with their catches, and the fur traders preferred to

visit the coastline briefly to trade European goods for animal skins trapped by the

Indians. But the kings of France had larger objectives: they planned to confront

and restrict the British as they attempted to dominate North America, and they also

hoped that the St. Lawrence River would ultimately lead to the fabled Northwest Passage

-

THE SETTLEMENT OF NEW FRANCE

To achieve their objectives, the French monarchs engaged a series of investors and

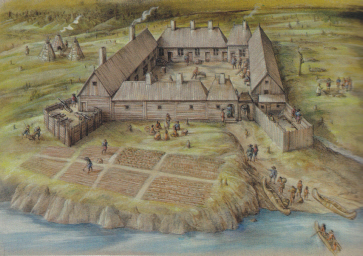

adventurers, some organized in joint- established a settlement in 1605 and spent the winter

there; in 1606 he was joined by our most notable ancestor, Louis Hébert. In 1608,

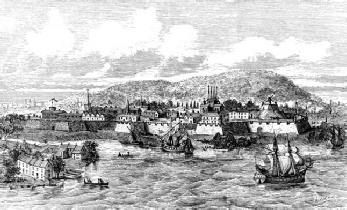

Champlain founded the first settlement on the St. Lawrence, at the site of Québec

City. In 1617, he established the first French settler family there: our ancestor,

Louis Hébert, this time accompanied by his wife, Marie Rollet, and their three children.

established a settlement in 1605 and spent the winter

there; in 1606 he was joined by our most notable ancestor, Louis Hébert. In 1608,

Champlain founded the first settlement on the St. Lawrence, at the site of Québec

City. In 1617, he established the first French settler family there: our ancestor,

Louis Hébert, this time accompanied by his wife, Marie Rollet, and their three children.

The settler population grew very slowly, however. The king required that merchants

bring settlers to Canada on each voyage, and he granted large estates there to noblemen

on the condition that they send peasants to cultivate the land. But it was not easy

to attract settlers to the distant colony, and the merchants and noblemen largely

evaded their commitments. So unattractive was the prospect of emigration that laborers

were given contracts that guaranteed them not only a competitive wage for a specified

period of time but also return passage to France. During the 1600s, nearly three-

By the late 1630s, there were barely 500 Frenchmen living in all of New France, mostly

single men, although a few married couples had been convinced to settle. Among them

were a dozen of our ancestors, farming land in and around Québec City. Then, in 1640,

a group of pious French noblemen and noblewomen received permission to found a new

settlement farther up the St. Lawrence River, on an island that was the site of periodic

markets where Indians traded furs for French manufactured goods. Their intentions

were entirely spiritual, in line with the intense Catholic Counter- Among the fifty men and women who arrived to establish the new

settlement in 1642 was our ancestor Augustin Hébert, whose name can be seen on the

monument to their achievement that stands today near the site of their first settlement.

They named the place Ville-

Among the fifty men and women who arrived to establish the new

settlement in 1642 was our ancestor Augustin Hébert, whose name can be seen on the

monument to their achievement that stands today near the site of their first settlement.

They named the place Ville-

Despite the ambitious plans of the founders of Montréal and the fact that, astonishingly, all of the settlers survived their first winter there, the new settlement initially failed to prosper. The Iroquois, who were then engaged in a series of wars with neighboring tribes to control trade on the St. Lawrence, killed many of the French settlers, and the founders were no more successful than previous recruiters in convincing young Frenchmen to come to this new and dangerous land. By 1652 the French population of Montréal was still just fifty, and the founders were on the verge of abandoning the project completely, but they decided to make one more effort to entice young men to join the settlement. The result was the celebrated “Great Recruitment,” which brought more than 100 men, as well as several women, to Montréal in 1653 and saved the project from extinction.

This early period in the history of Montréal is particularly important for our family

tree, since the largest single concentration of our immigrant ancestors were participants.

When the ship bearing the Great Recruitment arrived in 1653, eight of our ancestors

were among the fifty surviving settlers in Montréal who greeted it. Of the 57 members

of the Great Recruitment who ultimately established households and families in Montréal,

fifteen were our ancestors. By 1663, the population of the settlement had grown to

596; of this number, 49 were our ancestors. (Even today, after Montréal has become

a major world center, Duval descendants who visit will pass many cousins on the street,

especially in French-

While the survival of Montréal was encouraging, the king of France was profoundly disappointed with the rate of growth of his North American colony. The total population of French settlers on the St. Lawrence in 1663 was just 3,035, while the population of the British colonies to the south had already reached nearly 100,000. In that year he took the important step of assuming direct royal control of the entire colony, limiting the role of merchants to their trading activities.

Under the direction of the king, the following ten years saw a significant increase

in the population of New France. While individuals and couples were still occasionally

recruited by the noble landlords, the king took the lead by dispatching a regiment

of 1,200 young soldiers -

Then, in 1673, the king’s attention was once again drawn to Europe and to his conflicts

with the other major powers. Canada and its settlements declined in importance and

no longer received his direct support in colonization. Although small numbers of

immigrants continued to arrive, and another period of settlement occurred in the

mid-

During the entire period of colonization, from 1617 to 1760, around 22,000 French

men and women voyaged to the St. Lawrence Valley. The vast majority of these -

During the entire period of colonization, from 1617 to 1760, around 22,000 French

men and women voyaged to the St. Lawrence Valley. The vast majority of these -

The number of women who came to New France was much smaller, well under 2,000, and

almost none was indentured. Instead, they were recruited and financed by several

public and private programs intended to provide potential wives to the male settlers.

Since they had not been guaranteed return passage to France, and since they had nothing

to return to there in any case, nearly all of them -

From these humble beginnings -

WHO WERE OUR IMMIGRANT ANCESTORS ?

In general the 185 immigrants to New France who are the foundation of the Duval family

tree were representative of the early settler population as a whole. Three-

Their regional origins in France were typical of the general population of New France, in that almost all came from the west and northwest of France, areas that had long been involved with Atlantic commerce. Over half came from just three regions: Normandy, the areas around the western port of La Rochelle, and Paris. Most of the rest originated in nearby Brittany, Poitou, and Maine.

Most of the male immigrants had been trained in a craft, such as carpentry, masonry,

or shoemaking. In fact, it was the mobility and relative freedom that they had attained

in France as part of their training in a non-

Most of the male immigrants had been trained in a craft, such as carpentry, masonry,

or shoemaking. In fact, it was the mobility and relative freedom that they had attained

in France as part of their training in a non-

Although our immigrant ancestors were fairly typical of the Québec population, they

were exceptional in several ways. The most important of these was their relative

concentration in the Montréal area, which resulted from their significant involvement

in the early recruitment efforts there. By 1730, virtually all of our ancestral lines

were living in and around Montréal, either having settled there originally or having

migrated there from Québec City or other settlements on the St. Lawrence. Also important

was the absence of any immigrants later than 1710, even though at least one-

In general, our French Canadian ancestors did not come to the New World because of

poverty or religious persecution in Europe. Many were recruited by local noblemen,

the clergy, the army, or agents of the king. Some came in genuine support of the

religious mission of the Jesuits and other Catholic orders. Many came because it

offered a good job: of limited duration, well-

THE LIVES OF OUR ANCESTORS IN CANADA

The society established by France in Québec in the 17th century was essentially feudal

-

In French Canada, the king was embodied by the governor, established in comfortable

surroundings in Québec City, and by the intendent, who was the king’s administrative

representative. From the beginning of settlement, large tracts of land were granted

as fiefs (in exchange for fealty and hommage, as in the Middle Ages) to noblemen

and religious orders, called seigneurs, who were then expected to recruit peasants

and laborers to emigrate from France and settle on the land in order to make the

colony self-

The landscape was dominated by the St. Lawrence and by the rivers that flowed into

it. Unlike the familiar checkerboard pattern of farms or scattered villages in the

British colonies to the south,  virtually all farms in New France were long and narrow,

with the narrow end fronting on a river and with the family home and barn just a

few steps from the shore, occasionally interspersed with the parish church or the

larger home of the seigneur. In effect, the entire population was arrayed along the

rivers. While not efficient for purposes of defense, this arrangement permitted relatively

easy transportation throughout the year, by canoe or boat during the summer and by

sleigh during the long winter -

virtually all farms in New France were long and narrow,

with the narrow end fronting on a river and with the family home and barn just a

few steps from the shore, occasionally interspersed with the parish church or the

larger home of the seigneur. In effect, the entire population was arrayed along the

rivers. While not efficient for purposes of defense, this arrangement permitted relatively

easy transportation throughout the year, by canoe or boat during the summer and by

sleigh during the long winter -

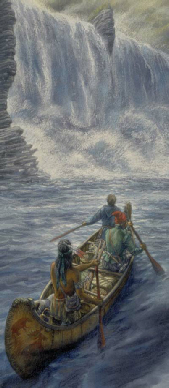

Apart from farming, by far the most important economic activity was fur trading,

mainly of beaver pelts, which were in great demand in Europe for the manufacture

of felt for hatmaking. The proceeds of the fur trade supported a small but prosperous

group of French Canadian merchants and provided enough in taxes and duties to finance

the colonial government in most periods. But most important for our ancestors, it

provided employment for large numbers of young men, who contracted with the merchants

of Montréal to travel by canoe to the Great Lakes and beyond to trade imported manufactured

goods to the Indians for beaver pelts. These year-

Apart from farming, by far the most important economic activity was fur trading,

mainly of beaver pelts, which were in great demand in Europe for the manufacture

of felt for hatmaking. The proceeds of the fur trade supported a small but prosperous

group of French Canadian merchants and provided enough in taxes and duties to finance

the colonial government in most periods. But most important for our ancestors, it

provided employment for large numbers of young men, who contracted with the merchants

of Montréal to travel by canoe to the Great Lakes and beyond to trade imported manufactured

goods to the Indians for beaver pelts. These year-

In addition to the fur trade, there were other elements that made life for common

people in early New France different from, and in many cases better than, life in

Europe. Farmland was much more abundant and could be obtained at a reasonable price,

and the French system of land tenure limited speculation. While fees, rents, tithes,

and labor were due to the seigneur and to the pastor, these were generally not onerous,

and there was no annual head tax -

Yet there were also hardships that gave pause to those who might have emigrated and thus limited the population of the colony. The ocean voyage was difficult and dangerous, even during peacetime, with significant numbers of passengers succumbing to disease en route. The Canadian winters were famously harsh and endless. For long periods during the early years, especially 1643 to 1667 and 1687 to 1701, colonists were vulnerable to attack by Iroquois warriors, who were notoriously cruel to their victims, as described in detail by the written narratives of Jesuit missionaries. (Five of our ancestors were killed by Iroquois raids during this period.) For these and other reasons, the population of New France always remained small: usually around five percent of that of the British colonies of North America.

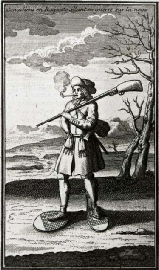

For the men of New France, armed conflict was very much a part of their lives. Throughout

much of the 17th century, they cultivated their fields in groups armed with muskets,

with several men standing guard as the others worked the crops. They had learned

that Iroquois raiders often lay in concealment for days on end, awaiting the opportunity

to seize an unwary colonist. Even during times of peace with the Indians, all men

were required to have firearms and to drill regularly as members of the permanent

militia. The relative lack of regular army troops in New France meant that it was

the peasants who were called out to participate in raids on the British and Dutch

settlements to the south and to defend against counterattacks. As militia members,

they fought beside the Indian allies of the French and learned their tactics of stealth

and ambush. In 1764, General James Murray, the first British governor of Québec,

reported that, “The Canadians are to a man soldiers.” While we lack details of specific

enlistments, we can be certain that many of our ancestors participated as combatants

in all of the major conflicts, including the French and Indian War (1754-

For the men of New France, armed conflict was very much a part of their lives. Throughout

much of the 17th century, they cultivated their fields in groups armed with muskets,

with several men standing guard as the others worked the crops. They had learned

that Iroquois raiders often lay in concealment for days on end, awaiting the opportunity

to seize an unwary colonist. Even during times of peace with the Indians, all men

were required to have firearms and to drill regularly as members of the permanent

militia. The relative lack of regular army troops in New France meant that it was

the peasants who were called out to participate in raids on the British and Dutch

settlements to the south and to defend against counterattacks. As militia members,

they fought beside the Indian allies of the French and learned their tactics of stealth

and ambush. In 1764, General James Murray, the first British governor of Québec,

reported that, “The Canadians are to a man soldiers.” While we lack details of specific

enlistments, we can be certain that many of our ancestors participated as combatants

in all of the major conflicts, including the French and Indian War (1754-

On balance, however, for those who came and settled in New France, life was relatively

prosperous and comfortable compared to that of their countrymen in Europe. Their

nutritional intake was higher, and they tended to be healthier and longer-

On balance, however, for those who came and settled in New France, life was relatively

prosperous and comfortable compared to that of their countrymen in Europe. Their

nutritional intake was higher, and they tended to be healthier and longer-

With few exceptions our ancestors were peasants who farmed lands that had been granted

to them on the estates of noble and church landlords. They were subsistence farmers

who produced for their own consumption and for sale to nearby towns, but they did

not seek to expand their farms or to produce a significant surplus, because French

mercantilist policy closed most external markets to them. With a relatively secure

home base, they married young and had many children, often more than ten or twelve

in each generation. The children received little education -

With few exceptions our ancestors were peasants who farmed lands that had been granted

to them on the estates of noble and church landlords. They were subsistence farmers

who produced for their own consumption and for sale to nearby towns, but they did

not seek to expand their farms or to produce a significant surplus, because French

mercantilist policy closed most external markets to them. With a relatively secure

home base, they married young and had many children, often more than ten or twelve

in each generation. The children received little education -

In fact, the benefits of life for the peasantry of New France over time tended to

make them remarkably conservative and resistant to change. Life was good and could

be maintained with a reasonable amount of work, and the typical peasant could provide

for his large family and see his children successfully married and settled on their

own farms. While agrarian reformers favored the abolition of feudalism, which had

in fact consigned much of European peasantry to poverty, French Canadian farmers

saw it as the reliable basis for their security. Crime and social disorder were relatively

rare and, in fact, substantially less common than in Puritan New England.

In fact, the benefits of life for the peasantry of New France over time tended to

make them remarkably conservative and resistant to change. Life was good and could

be maintained with a reasonable amount of work, and the typical peasant could provide

for his large family and see his children successfully married and settled on their

own farms. While agrarian reformers favored the abolition of feudalism, which had

in fact consigned much of European peasantry to poverty, French Canadian farmers

saw it as the reliable basis for their security. Crime and social disorder were relatively

rare and, in fact, substantially less common than in Puritan New England.

The British conquest of New France, in 1759-

The first fifty years of British rule brought unexpected economic benefits to the

French-

The first fifty years of British rule brought unexpected economic benefits to the

French-

It was not until the 1820s that population growth, due both to natural increase and

to immigration from Britain and Ireland, began to put pressure on land and resources.

It grew increasingly difficult for young men to find suitably sized plots of land

that they could afford, and a population of landless laborers began to rise, with

very little outlet or opportunity in Québec. During this period, our ancestors, who

had been born into families of farm owners, grew up instead to lives of day-

STORIES OF OUR ANCESTORS

LOUIS HÉBERT AND MARIE ROLLET

Louis Hébert, who is well-

Louis’ interest and involvement in the New World was inspired by Jean de Biencourt

de Poutrincourt, who had married Louis’ first cousin in 1590. Poutrincourt was the

scion of a distinguished and wealthy noble family of northern France who had decided

to expand his domain by establishing himself in the Americas. He toured the coasts

of Acadia (modern Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) during the summer of 1604, and in

February of 1606 he requested and was granted a fiefdom in Acadia by King Henri IV

on the condition that he establish a colony there. Poutrincourt proceeded immediately

to his task and in May of that year departed France on a well-

Poutrincourt’s companions, all young men, were no ordinary group of people. His vision

of his Acadian fiefdom was inspired by the world that he had known in France: a tightly-

Thus our ancestor set foot in the New World on July 27, 1606, when Poutrincourt’s

ship arrived at Port-

Thus our ancestor set foot in the New World on July 27, 1606, when Poutrincourt’s

ship arrived at Port-

During the fall of 1606, Poutrincourt and Champlain, accompanied by Louis Hébert and a small crew of sailors, explored the western shore of the Bay of Fundy (the coast of modern New England and New Brunswick) in search of appropriate sites for expansion of the colony. While they sought friendly relations with the local bands of Indians, they found that earlier European contacts had rendered them suspicious and sometimes hostile, especially as they sailed down the coast into the area that would later become Massachusetts. In early October they had a particularly close call, when they landed on the coast of Cape Cod, near modern Chatham, and set up a temporary encampment. During the night, five crew members, who had insisted on staying on shore despite orders to return to the boat, were attacked by a large group of Indians. Champlain and Louis Hébert, with others of the company, immediately rowed ashore and drove off the attackers, but four of the insubordinate sailors were killed.

The explorers then returned to Port- performed by the colonists, afloat in canoes and in full costume,

as the voyagers approached Port-

performed by the colonists, afloat in canoes and in full costume,

as the voyagers approached Port-

The winter of 1606-

Despite the evident success of this year of settlement in Port-

Arriving in Nova Scotia in the spring of 1610, the men began to rebuild the settlement

in Port-

While we have no evidence regarding Louis’ family during his extended absences in

the New World, it seems very likely that they became part of a network of the wives

and families of the men who had accompanied Poutrincourt to Acadia, including Poutrincourt’s

wife, Claude Pajot, who was Louis Hebert’s first cousin. Historians are not in agreement

as to whether Louis was in unbroken residence in Acadia between 1610 and 1614, but

he was there during most of the period, returning to France briefly if at all. Thus,

he had been away from France for five of the first twelve years of his marriage (1606-

Back in Paris in 1614 and once again established as an apothecary, Louis evidently grew restless. Although he continued to serve as solicitor for Poutrincourt’s son, he regretted being out of personal touch with the New World. When Samuel de Champlain, in Paris in 1617 to conduct business for the settlement that he had established at the future site of Québec City, proposed to him that he and his family move there, Louis evidently leapt at the opportunity. (We do not know his wife’s reaction.) Champlain approached the company of French merchants who then held a trading monopoly on the St. Lawrence, negotiating an agreement with them that the Hébert family would settle in Québec, with Louis to serve as their salaried employee and apothecary, with a small plot of land for farming. Louis soon arranged for the sale of his Paris property and proceeded with his family to the port of Honfleur in preparation for the voyage. While there, he learned to his astonishment that the merchant company had reneged on many of its commitments to him and reduced his promised salary by half. The merchants were, in fact, opposed to permanent colonists, who might seek to undercut their control of the fur trade and who might disrupt their crucial bartering relations with the Indians. However, since Louis had irrevocably sold his assets in France, he decided to proceed with the venture.

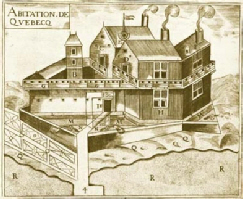

Louis, Marie, their three children, and their manservant arrived in Québec in July

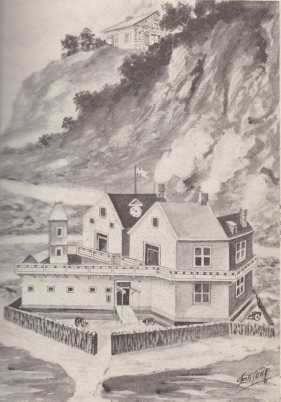

1617. The settlement had been in existence for nine years and still consisted of

a just few dozen men, most of them transient and involved in the fur trade, with

no women or children at all.  The Héberts erected a temporary dwelling near the official

residence (habitation) that Champlain had built in the lower part of the town near

the river, and within a few months they completed a stone house on the high bluff

above the habitation, not far from the location of the majestic Château Frontenac

today. They planted crops and a garden nearby, and Champlain was able to report the

following year that, “I visited the cultivated land, which I found planted and filled

with fine grain, the gardens full of all kinds of vegetables, such as cabbage, turnips,

lettuce, rhubarb, sorrel, parsley, and other plants, as well developed as in France.

In short, everything was manifestly prospering.”

The Héberts erected a temporary dwelling near the official

residence (habitation) that Champlain had built in the lower part of the town near

the river, and within a few months they completed a stone house on the high bluff

above the habitation, not far from the location of the majestic Château Frontenac

today. They planted crops and a garden nearby, and Champlain was able to report the

following year that, “I visited the cultivated land, which I found planted and filled

with fine grain, the gardens full of all kinds of vegetables, such as cabbage, turnips,

lettuce, rhubarb, sorrel, parsley, and other plants, as well developed as in France.

In short, everything was manifestly prospering.”

This was a substantial achievement, given that the merchant company had refused to allow the Héberts to have a plow. This impediment, plus the demands on Louis’ time for company business and for providing medical care to the settlement and the local Indians, limited the development of his farm. Although he was granted a small fief in 1623 (today the site of the basilica and the seminary in Québec City), which was ennobled and expanded in 1626, by the 1630s the Hébert family still had only six acres under crops. More important, however, Louis and Marie provided a vital center for the community. Their home was for years the finest private structure in the town, and residents gathered there regularly. In 1621 Louis was appointed king’s attorney, which made him responsible for conveying all laws, regulations, and public documents. He was always generous with his time, and Marie gave instruction in their home to the local children, both French and Indian. Still, it was a challenging and lonely existence; during the ten years following their arrival, just three more French families joined them in Québec.

In the winter of 1626, Louis was badly injured in a fall on the ice and never recovered.

He died on January 25, 1627. He left behind his widow, who remarried sixteen months

later, and his two surviving children: daughter Guillemette, who had married Guillaume

Couillard in 1621 and was to have ten children; and son Guillaume, who married Hélène

Desportes in 1634 and had three children before his untimely death in 1639 at the

age of 31. It is from the latter Guillaume’s daughter Françoise, born in 1638, that

we descend.

In the winter of 1626, Louis was badly injured in a fall on the ice and never recovered.

He died on January 25, 1627. He left behind his widow, who remarried sixteen months

later, and his two surviving children: daughter Guillemette, who had married Guillaume

Couillard in 1621 and was to have ten children; and son Guillaume, who married Hélène

Desportes in 1634 and had three children before his untimely death in 1639 at the

age of 31. It is from the latter Guillaume’s daughter Françoise, born in 1638, that

we descend.

In 1678, Louis’ remains were transferred with honor to the newly erected Recollet

chapel and were among the first to rest there. Today there is an impressive monument

to him and his family in Montmorency Park, beside the basilica in Québec City and

near the location of his first farm. There is also a plaque on the façade of his

birthplace in Paris, the shop/residence called the Mortier d’Or (Golden Mortar),

at 129 rue Saint-

NICOLAS MARSOLET

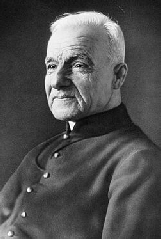

Our most colorful and controversial ancestor by far was Nicolas Marsolet: early companion of Champlain, one of the first Frenchmen to live year round in the St. Lawrence Valley, master of Indian languages, fur trader, merchant, and, ultimately, prosperous landowner and distinguished resident. His life illustrates some of the most dramatic episodes in the early history of Québec.

Samuel de Champlain, who is generally considered to be the founder of New France,

adopted a strategy of allying and cooperating with the Indian peoples of Canada rather

than attacking and subduing them. This was entirely a matter of necessity, since

it was clear to him that the French kings, who were deeply absorbed in the politics

of Europe, would never devote sufficient resources to the New World to support a

large French population and a conquering army. From the outset, therefore, Champlain

sent young men to live among the various Indian groups as truchements, which means

translator but much more as well: in the words of historian D.H. Fischer, these men

“were instructed to explore the country, live among the Indian nations, master native

languages, promote trade, build alliances, observe carefully, and report on what

they saw.” They were not typical agents of the French, however. In fact, they were

often traded to the Indians in a form of hostage exchange meant to ensure peace.

They were to live with the Indians, share their way of life, and support themselves

in the same way as their hosts. When Champlain and other French representatives wished

to communicate and negotiate with the Indians, they expected to be able to call on

these young men to step forward as well-

Nicolas Marsolet was born in Rouen, Normandy, in 1601 and was just twelve years old

when he was selected to be a truchement. In the spring of 1613 he departed France

aboard Champlain’s sixth voyage to North America.  Upon arrival, he was placed with

the Montagnais Indians of the Saguenay Valley, above Tadoussac, a trading settlement

on the St. Lawrence River. Here he was integrated into a selected family and shared

their lives in every aspect, and he evidently enjoyed it, finding their freedom,

expressiveness, adventure, and casual regard for authority to be preferable to his

experiences among his own countrymen. He learned to speak the Indians’ language,

to respect their customs, and to travel by canoe as they did, and he also learned

to support himself in their way, by hunting and fishing and by trading with distant

Indians for beaver pelts to exchange for manufactured goods imported by European

merchants on the St. Lawrence River.

Upon arrival, he was placed with

the Montagnais Indians of the Saguenay Valley, above Tadoussac, a trading settlement

on the St. Lawrence River. Here he was integrated into a selected family and shared

their lives in every aspect, and he evidently enjoyed it, finding their freedom,

expressiveness, adventure, and casual regard for authority to be preferable to his

experiences among his own countrymen. He learned to speak the Indians’ language,

to respect their customs, and to travel by canoe as they did, and he also learned

to support himself in their way, by hunting and fishing and by trading with distant

Indians for beaver pelts to exchange for manufactured goods imported by European

merchants on the St. Lawrence River.

For most of the preceding century, his Montagnais hosts had been at the center of

the fur trade. Their settlement at Tadoussac, relatively near the entrance of the

St. Lawrence, was a convenient port for French and other merchants, and the Montagnais

used this focal point to become prosperous middle- The Montagnais vigorously

protected their position by preventing the French from going up the Saguenay River

to make direct contact with their Indian trading partners.

The Montagnais vigorously

protected their position by preventing the French from going up the Saguenay River

to make direct contact with their Indian trading partners.

There was an inherent conflict between the interests of the Montagnais and the French

after 1600, the year in which the French first attempted to establish a permanent

trading post at Tadoussac. The French planned to settle colonies in the St. Lawrence

Valley, but they intended them to be self-

Marsolet, like many of his fellow truchements, eventually fell afoul of French Catholic missionaries, especially as the latter became more numerous in the area in the 1620s. The missionaries felt that the young Frenchmen, who tended to live morally casual lives and ignore the disapproval of the priests, were a negative influence on the Indians, creating an inappropriate image of French civilization and undercutting the missionizing efforts of the Church. In about 1626, the Jesuit fathers demanded that some of the truchements be expelled and returned to France, and Marsolet was evidently among them, providing another source of resentment toward the French authorities.

By 1629 Marsolet had found his way back to Tadoussac, where he was on the scene when

a fleet of British privateers commissioned by Charles I of England took possession

of the French St. Lawrence settlements under the misapprehension that Britain and

France were at war. Since the British offered a freer environment for trade and were

also willing to sell them liquor in exchange for beaver pelts -

Not surprisingly, Champlain accused Marsolet of treason, but he could take no action against him because he had surrendered New France and was now in British custody. To compound the offense, Marsolet testified against Champlain’s plan to take two young Montagnais Indian girls to France with him and was able to convince the British to deny Champlain his wishes, angering him even more.

The incident of Champlain and the Montagnais girls is worth examining in detail, since it has received considerable attention from historians and has tended to color their judgment of both Champlain and Marsolet. In Champlain’s telling, in 1627 he had adopted the two Indian girls, aged 11 and 12, at the request of their parents. He had taken them into his home, renamed them Hope and Charity, and cared for them under the watchful eye of local Catholic priests. When the British declared their intention to deport him to France in 1629, he requested that the girls accompany him, which, according to Champlain, they ardently desired to do. Marsolet spoke out against the plan, suggesting that Champlain’s intentions were less than honorable and that the girls’ parents were opposed to their going. In reply, Champlain lashed back at Marsolet, accusing him of lying and of wishing to have the girls for himself. The British listened to the dispute and ruled against Champlain; the girls stayed in Canada.

Since historians have tended to describe Champlain as nearly a saint, they have typically

judged that he was unfairly treated in this incident and that Marsolet was a scoundrel

or worse. But it is necessary to dissect Champlain’s self-

It should also be noted that sixteen years earlier Marsolet, then just twelve years

old, had spent two months aboard ship as Champlain’s cabin boy and may consequently

have learned some things about his attitudes and behavior toward children -

Finally, the judgment of the British privateers who ruled against Champlain should be dispositive. They were educated and sophisticated men of Champlain’s class who shared many of his experiences at sea and at war, and they displayed their personal affinity for him by treating him as their equal during his captivity, even to the extent of taking him on hunts with them. Yet they gave credence in this incident to Marsolet, who to them was little more than a servant. Perhaps most telling is the fact that Champlain himself never formally charged Marsolet with treason or any other crime, despite the fact that throughout this period, apart from his brief captivity by the British, he remained lieutenant general of New France and was fully empowered to take legal action. It is quite possible that Champlain avoided a formal, public airing of his charges against Marsolet lest it uncover inconvenient details that were inconsistent with his carefully cultivated image. While we will never know the exact circumstances of the affair of Champlain and the two Indian girls, we should certainly consider the likelihood that Marsolet acted honestly and honorably and that the final judgment of the British was justified.

Marsolet remained in New France during the British occupation but departed for France

before Champlain returned to Québec, in 1633, undoubtedly to avoid any repercussions

from their earlier unpleasantness. While in France he married Marie LeBarbier, and

in 1637 -

Marsolet died in 1677, leaving his widow and five surviving offspring of the ten who had been born to the family. We descend from his daughter Louise, born in 1640. As fortune would have it, the Marsolet surname would have died out, because there was no grandson to carry it on. But on the distaff side, several families chose to use it in place of their own, so the Marsolet surname lived on, in recognition of a distinguished ancestor.

HÉLÈNE DESPORTS

It is generally agreed that Hélène Desportes was the first child born of French parents in New France and therefore one of the first children born of European parents anywhere in North America. Although no baptism record has been found, it is known that she was born in Québec, that her godmother was Hélène Boullé, wife of Samuel de Champlain, and that Boullé arrived in Québec on 7 July 1620. Given her reported age in later records, Hélène Desportes was therefore born sometime between that date and the end of 1620. It is worth noting that her birth in Québec was within a few months of the landing of the Mayflower in Massachusetts.

Hélène’s parents were Pierre Desportes and Françoise Langlois, who had come to Québec from Normandy in about 1619, soon after their marriage. For the next ten years they were one of only five married couples living in Québec, the other four being Louis Hébert and Marie Rollet (also our ancestors), Abraham Martin and Marguerite Langlois (sister of Françoise), Guillaume Couillard and Guillemette Hébert (daughter of Louis Hébert), and Nicolas Pivert and Marguerite Lesage (the only couple not related to us).

When British privateers seized New France, in 1629, all of the families except the

Héberts and the Couillards elected to return to France, accompanied by Champlain.

While there, both of Hélène’s parents died, and she evidently came into the care

of her aunt, Marguerite Langlois, wife of Abraham Martin, with whom she returned

to Québec in 1633. In 1634 she married Guillaume Hébert, son of Louis Hébert. They

had three children before Guillaume’s untimely death, in 1639, including daughter

Françoise, born in 1638, from whom we descend. Also descending from Françoise was

her 5th great grandson, Alfred Bessette, born in 1845, who was canonized by the pope

in 2010 as Saint André of Canada. Saint André was a 5th cousin of Charles Duval and

therefore a cousin of all of us as well.

evidently came into the care

of her aunt, Marguerite Langlois, wife of Abraham Martin, with whom she returned

to Québec in 1633. In 1634 she married Guillaume Hébert, son of Louis Hébert. They

had three children before Guillaume’s untimely death, in 1639, including daughter

Françoise, born in 1638, from whom we descend. Also descending from Françoise was

her 5th great grandson, Alfred Bessette, born in 1845, who was canonized by the pope

in 2010 as Saint André of Canada. Saint André was a 5th cousin of Charles Duval and

therefore a cousin of all of us as well.

After Guillaume’s death, Hélène married Noel Morin, a wheel maker, with whom she

had twelve children, an experience that undoubtedly helped to qualify her for later

appointment as the town’s midwife. Among her children from this marriage, and therefore

distant cousins of ours, were Germain Morin, the first Canadian-

EARLY FAMILIES OF QUÉBEC

Apart from the five couples mentioned above in the discussion of Hélène Desportes, settlement in New France languished until the 1630s, when the Company of New France, which had been granted a trading monopoly by the king, began actively to recruit individuals and families to settle in the colony. The individuals were engaged by contract as laborers for several years, after which most of them returned to France. The families, on the other hand, were typically recruited by relatives or associates who were already involved in colonization, and they nearly all remained in Québec and established farms there. Over half of our earliest ancestors were among these families:

Marin Boucher and Perrine Mallet, settled in Québec by 1634

Nicolas Marsolet and Marie

LeBarbier, settled in Québec by 1637

Louis Sédilot and Marie Grimoult, settled in

Québec in 1637

Nicolas Pelletier and Jeanne de Vouzy, settled in Québec by 1637

Jean-

Jacques Archambault and

Françoise Tourault, settled in Québec by 1647

Jacques Badeau and Anne Ardouin, settled

in Québec by 1648

PIONEERS OF MONTRÉAL

As noted in the above historical narrative, our ancestors were especially prominent

in the founding of Montréal. The early history of the city is remarkable: establishment

of a religious outpost in 1642 at the very edge of the frontier by a small group

of determined settlers who received only warnings and discouragement from their contemporaries.

In that year 52 men and women, led by the pious nobleman Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve,

then just thirty years old, built a small wooden palisade on a spit of land in the

St. Lawrence, today called Pointe-

Augustin Hébert (unrelated to our other Hébert ancestor, Louis) had distinguished himself by behaving very differently than his peers. He had come from Normandy to Québec in 1637 as a soldier and stone cutter. But rather than return to France at the end of his enlistment, as most soldiers did, he elected to remain and to join the courageous group that set out to establish the settlement on Montréal Island in 1642. Then he went on to do something even more unusual: he returned to Paris to marry Adrienne Duvivier, in 1646, and then came back with her to Montréal. It is difficult to imagine the thought and deliberation that must have led to this action, given that the small settlement in Montréal had already acquired the reputation as a killing field for the Iroquois.

One assumes that Augustin had been deeply moved by the religious devotion of the

leaders of the project and was able to convince his bride to share the hardships

and sacrifice. And ultimately he did sacrifice his life, evidently abducted and killed

by the Iroquois in 1653. He left his young  widow and three children, including daughter

Jeanne, from whom we descend. He also left them the large plot of land that had been

conceded to him in 1648 by Maisonneuve -

widow and three children, including daughter

Jeanne, from whom we descend. He also left them the large plot of land that had been

conceded to him in 1648 by Maisonneuve -

Augustin Hébert was just one of many victims of Iroquois attacks during the early years of Montréal. Yet determined colonists continued to risk their lives in support of the community. Several of our ancestors joined the settlement during this period:

Jean Descaries arrived soon after the first group of colonists. By trade he was a

charbonnier - In 1650 Maisonneuve granted him

30 acres of land, bounded today by Boulevard René Lévesque, Rue de la Montagne, Rue

Versailles, and Rue William in downtown Montréal. Ten years later he was granted

a choice piece of land in the village, one acre near the market square, now called

Place Royale; the land today is on the north side of Rue St-

In 1650 Maisonneuve granted him

30 acres of land, bounded today by Boulevard René Lévesque, Rue de la Montagne, Rue

Versailles, and Rue William in downtown Montréal. Ten years later he was granted

a choice piece of land in the village, one acre near the market square, now called

Place Royale; the land today is on the north side of Rue St-

Blaise Juillet, from Avignon, came to Montréal in 1644 as an indentured laborer,

described as a bêcheur (ditch digger). After he had served his contracted term, he

remained in Montréal and was granted, in 1650, a plot of 30 acres of land, located

today along Rue Mansfield between Rue René Lévesque and Rue William in downtown Montréal.

In 1651 he married Anne-

Jacques Archambault and Françoise Tourault arrived in Québec by 1647, and within

a few years they and their six children joined the settlers in Montréal.  In 1651

Maisonneuve granted Jacques 30 acres of land adjacent to son-

In 1651

Maisonneuve granted Jacques 30 acres of land adjacent to son- Montréal. He was also granted a fine one-

Montréal. He was also granted a fine one-

Urbain Tessier arrived in New France in the mid- he was granted 30 acres of land, located today on the west side of Rue St-

he was granted 30 acres of land, located today on the west side of Rue St-

Despite the steady arrival of new colonists as well as a few births to settler families,

the population of Montréal did not grow at all for the first ten years because of

constant losses to the Iroquois. It still consisted of just fifty souls in 1651,

leading Maisonneuve to despair for the future. He returned to France, determined

to recruit at least 100 settlers to augment the colony or, failing that, to abandon

the project entirely. In the event, he was successful in both raising money and attracting

recruits. In July 1653, over 100 men and 15 women departed from Saint-

Michelle Artus

Jean Auger

Paul Benoît

Julien Daubigeon

Marin Deniau

Pierre Desautels

Jean

Gervaise

Louis Guertin

Marin Hurtebise

Catherine Lorion

Pierre Mallet

Perrine Meunier

Jacques

Milot

Hugues Picard

Jeanne Soldé

The first detailed census of Montréal was taken ten years later, in 1663, by which time the total French population had grown to 596. Of these, 49 were our ancestors, and they held substantial portions of land in the nascent city.

DAUGHTERS AND SOLDIERS

Despite the commitment and efforts of Champlain, Maisonneuve, and many other advocates and pioneers over more than half a century, New France failed to grow and prosper at the rate of the British and Dutch colonies to the south. In 1663, the total French population of the St. Lawrence Valley had reached just 3,035. By contrast, New England had nearly 40,000 European settlers, New Netherland 9,000, Maryland 6,000, and Virginia 35,000. In that year, fresh impetus was given to the colonizing of New France by the young and vigorous French king, Louis XIV. Having for the moment settled European matters to his satisfaction, he took renewed interest in his languishing North American colony. He dismissed the merchant company that had failed to bring it prosperity and assumed direct responsibility for administration and colonization.

Concerned especially that the small French population continued to be vulnerable

to Iroquois attacks and that this was a major impediment to further settlement, the

king ordered that the Carignan-

Concerned especially that the small French population continued to be vulnerable

to Iroquois attacks and that this was a major impediment to further settlement, the

king ordered that the Carignan-

Etienne Charles

Bernard Deniger

René Dumas

Germain Gauthier

Hilaire Limousin

Louis Marier

Nicolas

Moison

Louis Robert

François Séguin

The king was no less concerned that the population of New France was heavily unbalanced

in favor of men and that it would not endure unless women could be made available

to marry and form families. He thus ordered that his agents recruit young women of

respectable parentage and  backgrounds, mostly from the area in and around Paris,

many of them orphans who had been raised by religious orders. Between 1663 and 1673,

770 young women, called Filles du Roi (King’s Daughters), were transported to New

France under this program. Upon arrival, they were placed under the strict supervision

of local nuns, who oversaw their introduction to eligible young men, and within a

few months virtually all were successfully married. The King’s Daughters constituted

nearly half of all the women who immigrated to New France and so became the firm

and broad base of the French-

backgrounds, mostly from the area in and around Paris,

many of them orphans who had been raised by religious orders. Between 1663 and 1673,

770 young women, called Filles du Roi (King’s Daughters), were transported to New

France under this program. Upon arrival, they were placed under the strict supervision

of local nuns, who oversaw their introduction to eligible young men, and within a

few months virtually all were successfully married. The King’s Daughters constituted

nearly half of all the women who immigrated to New France and so became the firm

and broad base of the French-

Anne Aubry

Jeanne Bernard

Jeanne Bilodeau

Marie Barbe Boyer

Louise Charrier

Jeanne Denot

Catherine

Ducharme

Mathurine Goard

Anne Grimbault

Madeleine Groleau

Marie-

Marguerite

Laverdure

Marguerite Leclerc

Antoinette Lefebvre

Marie Lelong

Catherine Lemesle

Catherine

Moitié

Madeleine Niel

Catherine Paulo

Jeanne Petit

Marie Anne Rabady

Marguerite Raisin

Georgette

Richer

Marguerite Richer

Anne Roy

Jeanne Servignan

Marguerite Vaillant

There are, of course, millions of descendents of the daughters and soldiers today

in Canada and the United States, including us. Descendants are eligible to join La

Société des Filles du roi et soldats du Carignan, a kind of low-

ADRIEN ST. AUBIN

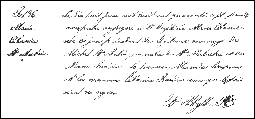

Our St. Aubin line began in the New World with the arrival in Montréal in about 1665

of seventeen-

In 1680 Adrien married Jeanne-

ANNETJE CHRISTIAANSZ AND MOÏSE DUPUIS

Moïse Dupuis was born in Québec on 8 July 1673, the second child of immigrant parents

who later settled in Laprairie, near Montréal. As a teenager Moïse followed the path

taken by many young Frenchmen in Canada and became a coureur-

Annetje Christiaansz, according to the findings of reputable researchers, was probably

the out-

What do we know of Annetje’s parents? Her father, Christiaan Christiaansz, was born in the Netherlands in about 1640 and arrived on the Hudson River in 1659, where he had been hired as an indentured laborer by the prominent van Rensselaer family of Rensselaerswyck, near Albany. By 1671 he completed his indenture and purchased a small plot of land in Schenectady, which was then a community of fewer than 200 settlers on the frontier of Mohawk country. He was still a junior member of the community five years later when Annetje was born.

Annetje’s mother, whose name we do not know, was of African descent and undoubtedly

a slave. At that time there were about a dozen African slaves in Schenectady, most

of them female, engaged in domestic and farm labor for individual families. It is

likely that she had been imported from one of the plantation settlements in the Caribbean

-

Edgar McManus, the leading authority on slavery in New Netherland, notes that the Dutch were largely free of racial prejudice and treated their slaves in much the same way as they treated indentured European workers, as an expensive source of labor to be sensibly exploited but not abused: “Despite their unequal relationship, masters and slaves worked together at the same tasks, lived together in the same houses, and celebrated the Dutch holidays together on terms of easy familiarity.” We do not know if she and Christiaan were more than casual acquaintances. It is unlikely that he owned her, since he was not yet wealthy enough to afford the current price of a slave, which was about one year’s wages for an adult male worker. But he may have leased her, a common practice at that time.

Soon after their marriage, in 1697, Annetje and Moïse moved to Québec, where in 1699 she was baptized in the Catholic Church and given the names Marie Anne Louise. The couple settled in Laprairie, near Moïse’s parents, and had nine children, most of whom survived to adulthood. We descend from their daughter Barbe, born in 1715. Both Moïse and Annetje died in 1750.

PIERRE EDMÉ THUOT DIT DUVAL

The first Duval of our line in New France was Pierre Edmé Thuot dit Duval, born in

1681 in Tonnerre, a town in Burgundy about 120 miles southeast of Paris . He was a

son of master baker Edmé Thuot, who in 1668 had married Marie Louise Duval, daughter

of François Duval, a huissier royal (royal bailiff). With this match, Edmé took a

definite upward social step in class-

. He was a

son of master baker Edmé Thuot, who in 1668 had married Marie Louise Duval, daughter

of François Duval, a huissier royal (royal bailiff). With this match, Edmé took a

definite upward social step in class-

Pierre was, interestingly, the next to last of our 185 immigrant ancestors to arrive

in New France. By 1709 he was in Montréal, which we know because he fathered an illegitimate

child there who was born early the following year. By 1712 he was established in

Montréal as a master baker, and in that year he married Marie Fournier. Marie was

a granddaughter of an immigran t from the town of Irancy, which is just twenty miles

from Tonnerre, and it is possible that this connection sheds light on Pierre’s decision

to immigrate to New France, given that very few settlers otherwise came from this

part of France.

t from the town of Irancy, which is just twenty miles

from Tonnerre, and it is possible that this connection sheds light on Pierre’s decision

to immigrate to New France, given that very few settlers otherwise came from this

part of France.

Pierre and Marie moved between Montréal and Québec City several times, which suggests

that his baking enterprise may have been more than just a single shop. Between 1713

and 1725 they had ten children, the last of whom was Thomas Ignace, great-

CHARLES, SARAH, AND THEIR CHILDREN

CHARLES DUVAL, 1843-1924

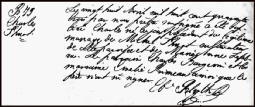

Charles Duval was born on 27 April 1843 in Ste-

Charles Duval was born on 27 April 1843 in Ste-

It is important to note that the surname given to Charles at baptism was not Duval

but rather Thuot (pronounced TYOO- preferred to call themselves

Thuot. It was only later in life that Charles chose to use Duval exclusively as his

surname, probably because it was easier for English-

preferred to call themselves

Thuot. It was only later in life that Charles chose to use Duval exclusively as his

surname, probably because it was easier for English-

In the late 1840s, Charles’s family moved to the nearby village of Beauharnois and

then by 1849 settled in St-

In early 1858, at the age of 14, Charles set off, probably with a group of relatives

and friends, to find work in the United States. He entered at the port of Detroit

and probably stayed in the area for a while as a farm worker and perhaps as a carpenter

and construction worker, for which he had received some training. Before long, however,

he returned to Canada, probably to avoid conscription by the Union army in the U.S.

Civil War. In 1861, he was again with his parents in Québec, in the village of St-

In 1865, at the age of 21, Charles married for the first time, in the parish church

of St-

In 1865, at the age of 21, Charles married for the first time, in the parish church

of St-

In 1871 Charles was living in St-

By this point in his life, Charles, like hundreds of thousands of his fellow French

Canadians at that time, had decided to emigrate to the United States, where both

land and employment opportunities were far more abundant than in Québec. In preparation

for emigration, he traveled to the United States and may have devoted as much as

a year to exploring possible destinations. While the great majority of French Canadian

emigrants moved to New England, Charles chose instead to settle in central Wisconsin,

near the village of Unity, on the border between Clark and Marathon counties. While

his reasons for selection of this village are not known, it should be noted that

a few French Canadian families were already settled there and that Charles may have

previously been in communication with them. During his absence in the United States,

Charles left his two daughters in the care of his mother-

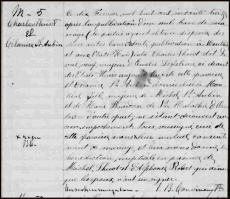

By early 1873 Charles had returned to Québec. On February 10th of that year, in the

parish church of St-

By early 1873 Charles had returned to Québec. On February 10th of that year, in the

parish church of St- greement make it clear that this was

unlikely to happen and that it was intended that they remain permanently with their

grandmother and uncle in Québec, which they ultimately did.

greement make it clear that this was

unlikely to happen and that it was intended that they remain permanently with their

grandmother and uncle in Québec, which they ultimately did.

By the middle of the year 1873 Charles and his wife Célanire, who called herself Sarah after settling in Wisconsin, had arrived near Unity and had rented a house and probably a small farm, where Charles could both cultivate crops and engage in his trade of carpentry and construction work. In December their first child, Charles, was born. Over the following twelve years eight more children were born, all but one of whom survived to adulthood. By 1880 Charles and Célanire had been joined in Wisconsin by four members of Charles’s family: his father Michel, his mother Marie Anne (née Lefebvre), and his younger siblings Philomène, who married Hubert Beaudin in about 1875, and Alexis, who married Delia Leclaire in Dorchester, Wisconsin, in 1880.

In 1877 Charles purchased his first significant piece of real estate, 160 acres in Brighton, Marathon County, just to the east of Unity. In 1888, by which time he and Célanire had moved to Marshfield, Wood County, he sold the land in Brighton and then in 1889 purchased 160 acres just southwest of Unity, in Clark County. In 1897 he lost this property in foreclosure and moved to a rented farm near Unity, where his main source of income again became carpentry and construction work. Soon after 1900 he moved to forty acres of farmland that he had purchased in McMillan, Marathon County, to the east of Unity, where he and Célanire lived for the rest of their lives.

Charles died on 21 May 1924 in Marshfield, Wisconsin, from injuries suffered from falling down a stairway at the home of his granddaughter Julia Duval on her wedding day.

SARAH DUVAL (MARIE CÉLANIRE ST. AUBIN), 1847-1924

Marie Célanire St. Aubin, whom her children and grandchildren knew as Sarah, was

born on 18 June 1847 in the village of Ormstown, Québec, about twenty miles south

of Montréal. She was a daughter of Michel St. Aubin and Marie Bourdon, who had been

married in the nearby town of Chateauguay in 1840. Michel and Marie had seven children

between 1841 and 1854, six of whom survived to adulthood.

Marie Célanire St. Aubin, whom her children and grandchildren knew as Sarah, was

born on 18 June 1847 in the village of Ormstown, Québec, about twenty miles south

of Montréal. She was a daughter of Michel St. Aubin and Marie Bourdon, who had been

married in the nearby town of Chateauguay in 1840. Michel and Marie had seven children

between 1841 and 1854, six of whom survived to adulthood.

Since Célanire’s father was a laborer, the family moved frequently from village to

village in the rural area south of Montréal as he sought work. Over the years, they

lived in Ste- her twenty-

her twenty-

On 10 February 1873, she married Charles Duval in St-

In the United States, Célanire soon began calling herself Sarah, perhaps because

her real name was unfamiliar to her new, English-

soon began calling herself Sarah, perhaps because

her real name was unfamiliar to her new, English-

Like Charles, Célanire never learned to read or write.

Célanire/Sarah died on 22 March 1924 in McMillan, Marathon County, from complications of diabetes.

THE CHILDREN OF CHARLES AND SARAH

Charles, the first child of Charles and Sarah, was born in Unity on 19 December 1873

and baptized five months later at St. Stephen’s in Stevens Point, which was the nearest

Catholic church to Unity at that time. In 1893 in Colby, Clark County, he married

Mary Elizabeth Rocheleau, daughter of French-

Charles, the first child of Charles and Sarah, was born in Unity on 19 December 1873

and baptized five months later at St. Stephen’s in Stevens Point, which was the nearest

Catholic church to Unity at that time. In 1893 in Colby, Clark County, he married

Mary Elizabeth Rocheleau, daughter of French-

CHILDREN OF CHARLES AND MARY (ROCHELEAU) DUVAL

Leo Charles Duval, 1893-

Leo Charles Duval, 1893- Edwin Thomas Duval, 1896-

Edwin Thomas Duval, 1896-

Clara Loretta Duval, 1898-

Clara Loretta Duval, 1898- Ozilda Mary Duval, 1901-

Ozilda Mary Duval, 1901-

Laura Loretta Duval, 1903-

Laura Loretta Duval, 1903-

Emery Michael Duval 1906-

Lawrence Frank Duval, 1909-

Agnes Elnora Duval, 1912-

Ione Violet Duval, 1917-

MARIE MAUDE DUVAL, 1875-after 1930

Maude, the oldest daughter of Charles and Sarah, was born in Unity on 12 January 1875 and baptized three months later at St. Stephen’s in Stevens Point. In 1889 in Colby she married Joseph Paquin, with whom she evidently had no surviving children. Joseph died in about 1895, and in 1896 in Marshfield, Wood County, she married William Adelbert Sheldon, with whom she had one son. By 1910 the family had settled in Harlowton, Montana. William died in Montana between 1920 and 1930, and Maude was still living in Harlowton in 1930, supporting herself by taking in lodgers.

MARCIAN THEODORE (CLAUDE) DUVAL, 1876-1952

Marcian Theodore, the third child of Charles and Sarah, who called himself Claude, was born in Unity on 14 March 1876 and baptized two weeks later at St. Stephen’s in Stevens Point. By 1900 he had moved to Montana and settled in Gilt Edge, Fergus County. By 1920 he was in Everett, Washington, working as a railroad car repairer. By 1930 he had moved to South Lake Stevens, Washington, and was working on a farm. Although he married twice, he was evidently childless. He died in Hewitt, Wood County, Wisconsin, in 1952.

THOMAS DUVAL, 1878-1963

Thomas, the fourth child of Charles and Sarah, was born in Unity on 23 May 1878 and baptized ten weeks later at St. John’s Catholic Church in Marshfield. His godparents were Michel Thuot dit Duval and Marie Anne Lefebvre Duval, his grandparents, who had by then joined Charles and Sarah in Wisconsin. By 1900, he had settled in Rondell, South Dakota, where in 1901 he married Minnie Dayton, with whom he had three children between 1902 and 1908. The family moved to Fergus County, Montana, by 1920, and Thomas continued to work as a farmer. Minnie died there, in the town of Lewiston, in 1962, and Thomas died the following year.

LOUIS ALFRED (FRED) DUVAL, 1879-after 1930

Louis Alfred, the fifth child of Charles and Sarah, who called himself Fred, was born in Unity on 1 September 1879 and baptized two months later at St. John’s Catholic Church in Marshfield. He remained in Wisconsin, close to his parents, and in about 1906 he married Marie Hebert. They had six children between 1908 and 1918. We lose track of him in later records, but it may be he who is found in 1930 in La Plata County, Colorado, living alone as a boarder (though married) and employed as a farm laborer.

FRAN CIS XAVIER (FRANK) DUVAL, 1880-

CIS XAVIER (FRANK) DUVAL, 1880-1951

Francis Xavier, the sixth child of Charles and Sarah, who called himself Frank, was

born in Unity on 1 December 1880 and baptized eight months later at St. John’s Catholic

Church in Marshfield. His godparents were his uncle François Xavier St. Aubin and

his aunt Marie Marguerite St. Aubin, who by this time had joined Charles and Sarah

in Wisconsin. In 1909 in Marshfield Frank married Alma Stella Boucher, daughter of

French-

Francis Xavier, the sixth child of Charles and Sarah, who called himself Frank, was

born in Unity on 1 December 1880 and baptized eight months later at St. John’s Catholic

Church in Marshfield. His godparents were his uncle François Xavier St. Aubin and

his aunt Marie Marguerite St. Aubin, who by this time had joined Charles and Sarah

in Wisconsin. In 1909 in Marshfield Frank married Alma Stella Boucher, daughter of

French-

CHILDREN OF FRANK AND STELLA (BOUCHER) DUVAL

Michael Lloyd Duval, 1910-

Michael Lloyd Duval, 1910- Pearl Victoria Duval, 1918-

Pearl Victoria Duval, 1918- Gordon Louis Duval, b.1923

Gordon Louis Duval, b.1923

MICHAEL ANDREW DUVAL, 1882-1925

Michael, the seventh child of Charles and Sarah, was born in Unity on 28 December 1882 and baptized five weeks later at St. John’s Catholic Church in Marshfield. His godparents were his aunt Marie Marguerite St. Aubin and her husband David Viau, who had recently married. As Michael grew up, he developed into an attractive, intelligent, ambitious, and hard working man, but he wasn’t the kind of person who would get a steady job and meticulously climb the ladder of success. Instead, he was restless and was always looking for an angle and for a way to make his fortune. He clearly enjoyed life and people and liked to have a good time.

He left school  early, as did almost everyone at that time, and by the age of sixteen

he was working as a lumberjack. His first big opportunity occurred when he met Elizabeth

(Lizzie) Beaver and convinced her to marry him. He recognized in her a person who

was his total opposite -

early, as did almost everyone at that time, and by the age of sixteen

he was working as a lumberjack. His first big opportunity occurred when he met Elizabeth

(Lizzie) Beaver and convinced her to marry him. He recognized in her a person who

was his total opposite -

For several years Michael produced and delivered cheese, and he even managed to invent

a device for improving the efficiency of cheese manufacture,  which he patented, but

he never realized any benefit from the invention, possibly because the potential

market was too small. It seems as well that he thought of himself as an inventor,

because he devoted some effort to one of the great fantasies of that time, the discovery

of a “perpetual motion” machine, which would run forever on its own momentum, without

fuel. The successful inventor of such a machine would, of course, be wealthy beyond

his dreams.

which he patented, but

he never realized any benefit from the invention, possibly because the potential

market was too small. It seems as well that he thought of himself as an inventor,

because he devoted some effort to one of the great fantasies of that time, the discovery

of a “perpetual motion” machine, which would run forever on its own momentum, without

fuel. The successful inventor of such a machine would, of course, be wealthy beyond

his dreams.

By 1920, Michael had disposed of the cheese factory and was in the business of upholstering

furniture. In 1921, he left that work and opened a shop with his brother Charles

at 327 North Central in Marshfield that distributed auto batteries, carburetors,

and tires. (His brother in law Philip Beaver operated an auto repair shop at the

same address.) But at this point a new opportunity came his way. The enactment of

the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, in 1920, prohibited the manufacture

and sale of alcoholic beverages. Men in rural communities across the country saw

an opportunity -

By about 1922 Michael had moved his family a few miles outside of Marshfield to a

rented farm and was manufacturing and selling moonshine. It was evidently an open

secret that he was engaged in this activity, and it is likely that local law enforcement

officers enjoyed his products and perhaps even received a share of his profits. The

money rolled in, and soon Michael was looking for a way to invest it and build his

fortune.

By about 1922 Michael had moved his family a few miles outside of Marshfield to a

rented farm and was manufacturing and selling moonshine. It was evidently an open

secret that he was engaged in this activity, and it is likely that local law enforcement

officers enjoyed his products and perhaps even received a share of his profits. The

money rolled in, and soon Michael was looking for a way to invest it and build his

fortune.

Prohibition brought many changes in the 1920s in America. Although it was well intentioned, it led to the rise of a vast underworld serving the public’s unquenchable thirst for alcohol. Organized gangs, most notably the mafia, smuggled bottled liquor into the country in great quantities; amateur distilleries were built across the country; and entrepreneurs in every town and city opened speakeasies, where paying customers could get a drink and have a good time. Urban centers, such as Chicago and New York, witnessed the rise of a new class of wealthy men, who made their fortunes from this trade and liberally spread their wealth to those who surrounded and served them.

Wisconsin became a special beneficiary of the new prohibition wealth when Chicago gangsters discovered the attractions of the lakes in the northern part of the state, near Rhinelander. Soon, their vacation retreats began to appear on the lakeshores, and speakeasies and other establishments were opened to serve a new class of customers.

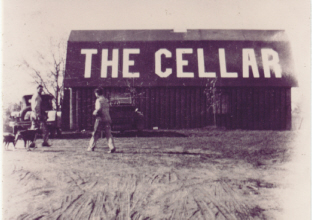

Michael, always open to new opportunities, and now in possession of his moonshining

profits, traveled to Rhinelander, scouted the surrounding area, and in 1925 purchased

a plot of land on a lake to the west of nearby Woodruff.  In August of that year,

he began construction of a two story building near the lake that was to be a nightclub

(and speakeasy) as well as a new home for his family. In November, as the building

was nearing completion, he brought his family up from Marshfield to join him.

In August of that year,

he began construction of a two story building near the lake that was to be a nightclub

(and speakeasy) as well as a new home for his family. In November, as the building

was nearing completion, he brought his family up from Marshfield to join him.

On the evening of Sunday, December 20, the day that the family moved from the old house on the property to the new house, Michael gathered a few friends to celebrate, drink, and play music. (Michael himself played the violin.) Among the friends was Charles J. (Charley) Rey, who had come up from Marshfield the previous day by train and had spent the night with the family.

Charley Rey was a nearly illiterate laborer who was, at that time, 67 years old and

therefore 25 years older than Michael. In about 1915 he had moved from his native

Michigan to Marshfield, where he got a job as a street sweeper for the town. In the

early 1920s -