Welcome! This site is devoted to Priesmeyers everywhere and to their rich family history. If you are a member of the clan, you can learn about your ancestry, reaching back to the 16th century, and discover how you are related to your many Priesmeyer cousins around the world. And you can read stories and see photos of your branch of the family, adding your own if you like.

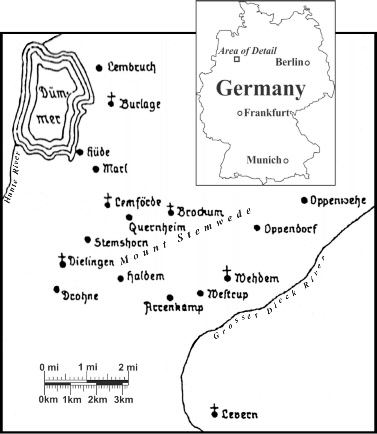

- Nearly all Priesmeyers today, whether in America or in Europe, are direct descendants of one household in northern Germany: farm number 3 in the village of Oppenwehe. The documented ancestry of the lineage and its many branches extends from this origin in an unbroken line from the late 1500s to the present.

- Nearly all Priesmeyers today, therefore, are provably related to each other, although often quite distantly.

- During the great wave of German immigration in the nineteenth century, 46 adult Priesmeyers

-

- 36 men and 10 women - - came to America, most of them between 1848 and 1882. Eighty percent settled in the Midwest, mainly in St. Louis, while the rest chose rural east Texas.

- Despite the predominance of immigrants to the Midwest, their descendants today comprise fewer than half of the Priesmeyers in America. The Texas branches were far more prolific, having chosen the farming life, with its large families, in contrast to their urbanized cousins in St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland, and Cincinnati.

- The banner at the top of this page pictures notable Priesmeyers against a backdrop

of Mount Stemwede, near Oppenwehe. The stylized writing in the center is the family

name -

- spelled “Prissmeier” - - as written by the pastor in recording the 1665 marriage of Heinrich Priesmeyer and Anne Alheit Hilmer, direct ancestors of most Priesmeyers in America today.

If you’d like to know more, read on . . .

OPPENWEHE: THE PRIESMEYER HOME TOWN

Oppenwehe is a small farming village in northwestern Germany not far from the city

of Osnabrück. It sits on the sandy soil of the great Saxon plain and has a current

population of just over two thousand. As agricultural land it has always been marginal,

best suited to grazing animals and growing flax. Historians and archeologists agree

that it was first settled by Saxons, though sparsely, during the period from 500

to 800 AD. Following Charlemagne’s conquest and conversion of the Saxon tribes in

the late 8th century, the existing settlements were awarded to his secular and religious

retainers as feudal estates.

Thereafter the peasant settlements were devoted primarily to making the land productive

so as to provide revenues to support their noble and church landlords. At first,

each village was centered on one peasant and his family, usually called Meyer, following

a Roman model. The Meyer farm became the nucleus of a group of families who farmed

the land, submitted a portion of their produce to the Meyer for safekeeping, and

were then required to assist in transporting it to the landlord. In 1227, the first

mention of Oppenwehe in the documents, four of the farms and the families living

on them were sold by their noble landlord, Helimbert von Manen, to the newly-

We know nothing, unfortunately, about the very earliest Priesmeyers, except that their farm was located on a plain, called the Röhe, from which they acquired an alternate surname, “achter den Röhen,” in use until the early 1600s, when it was fully replaced by Priesmeyer. We cannot even be sure that the Priesmeyers who emerged into the historical record in the early 17th century were direct descendants of the earliest settlers, since, as we’ll see later, surnames initially associated with farms persisted, even if the original settler family died out and was replaced by an entirely new family. But we do know that the Priesmeyer lineage established by about 1570 has been in unbroken possession of the family farm at Oppenwehe 3 until the present and is the origin of nearly all Priesmeyers today.

The earliest farms settled were typically the largest, with between forty and eighty acres, plus access to common grazing land. The soil was sown with various kinds of grain, especially rye, and with grasses for fodder. Each of the large farms had a pair of horses for plowing; several cows, pigs, and sheep; and innumerable geese and chickens. While farming methods cannot be called scientific, the peasants were aware of the value of fertilizing their land and of letting parts of it lie alternatively fallow. Farm houses and barns were not clustered together for protection, as was customary in other parts of Germany, but rather were dispersed in order to be close to the family’s main fields. Farming plots were usually long and narrow, reflecting the relative convenience of plowing without having to turn the team frequently.

Over time, the population of Oppenwehe and of all of the villages in the area grew

and declined in response to the success of harvests and, especially, due to periodic

epidemics. The Black Death of the 14th century devastated large parts of Germany,

but by 1600 the population had reestablished itself to levels reached before the

plague, only to be dealt another massive blow by the Thirty Years War, from 1618

to 1648. The armies of several kingdoms marched and countermarched across central

Europe, pillaging, raping, seizing crops, and killing at will anyone who impeded

their progress. In some parts of Germany as many as two-

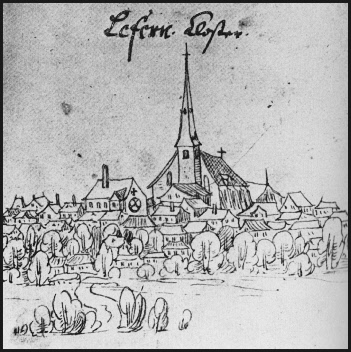

As noted above, nearly all of the villages and the constituent farms (and their farming

families) were the property of noble or church landlords. By the late Middle Ages

most of Germany, which was itself divided into many kingdoms and principalities,

had become a patchwork of thousands of intermingled and overlapping landholdings,

as landlords exchanged parts of their properties with each other to settle debts,

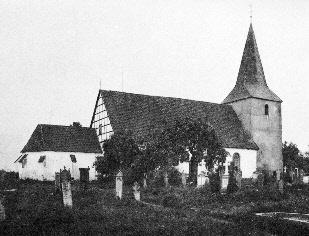

to fulfill pledges, or, they hoped, to purchase their way into heaven. From 1235,

as we have seen, all of Oppenwehe was the property of the Cistercian convent in Levern,

seven miles to the southwest, as depicted here in the year 1632. From that time forward,

each peasant family was required to submit a portion of its annual produce to the

convent to support the religious community. Even after the Protestant Reformation,

when the convent was converted into a “freiweltliches Dammenstift” -

debts,

to fulfill pledges, or, they hoped, to purchase their way into heaven. From 1235,

as we have seen, all of Oppenwehe was the property of the Cistercian convent in Levern,

seven miles to the southwest, as depicted here in the year 1632. From that time forward,

each peasant family was required to submit a portion of its annual produce to the

convent to support the religious community. Even after the Protestant Reformation,

when the convent was converted into a “freiweltliches Dammenstift” -

When the Priesmeyer name first appeared in written documents, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the family farm, at Oppenwehe 3, was held by Heinrich Priesmeyer, born in about 1570. As he approached his 60s and retirement, he appealed successfully to his landlord to permit him to pass the family farm to his daughter, Catharine, and to her intended husband, Heinrich Mundt, of Oppenwehe 36. This appeal suggests that she was not the heir originally preferred by Heinrich Priesmeyer and his landlord; rather, the intended heir was probably a son born in about 1605. We don’t know what prevented this son from inheriting, although it may be suggested that he had enlisted for military service during the Thirty Years War and had never returned home.

In any case, Catharine Priesmeyer and Heinrich Mundt were married in 1636 and took

possession of the Priesmeyer farm. In accordance with regional custom, Heinrich adopted

the Priesmeyer surname, and thus it was passed on to their descendants. The couple

had at least five children, and their oldest son, Thomas, born in about 1635, was

eventually chosen to inherit the farm, with the approval of their landlord. As Thomas

approached his marriage, and therefore the receipt of his inheritance, including

the farm, his parents took a relatively unusual step for the time: they established

their two other sons on new farms of their own, carved out of the original family

farm. Normally these sons would have been limited to just a moderate cash bequest

to facilitate marriage to farm-

I Thomas Priesmeyer and my parents declare that we wish to give our sons Gerd Heinrich and Heinrich Priesmeyer each 60 talers in cash from our farm and 6 talers for cattle, and each a horse and a suit of clothes to hold for their wedding day; also to Gerd Heinrich a piece of land of two Scheffelsaat [about two acres] by Johann Spreen’s plot in the Röhe, and to Heinrich two pieces of land of four Scheffelsaat [about four acres] on the Westhoue; and to give the daughter what Marie [Thomas’s fiancée] brings with the dowry; and to pay for a Freibrief [marriage release] or Weinkauf [marriage fee] for the children.

Present as witnesses: Gerd Meyer, Johann Spreen, Johann Bosse.

Oppenwehe, 14 August 1662.

The resulting new farms, which were given the numbers 47 and 50 in Oppenwehe, were

initially quite small, although they grew substantially as later generations added

to them. Thirty years later, Thomas’s oldest son, Martin, born in 1664, also established

a new farm in Oppenwehe, which was given the number 53. Each of the resulting four

Priesmeyer farms in Oppenwehe -

In the census of 1682 we have a snapshot of the first three of the four farms. Oppenwehe

3, headed by Thomas Priesmeyer, which was the original family homestead, was fairly

large, at about 55 acres plus access to common grazing land. Major livestock consisted of two horses, four cows, eighteen sheep, and a sow. Each year the family was required

to submit ten percent of their produce to their landlord, Stift Levern, and to provide

transportation to its storehouses. They also owed annual obligations to three separate

civil authorities, Amt Rahden, Amt Levern, and Amt Lemförde. In total, these civil

obligations consisted of another tenth of the produce of their farm, plus several

sheep and hens, a moderate amount of cash, and about ten days of compulsory labor

on roads, public buildings, and transportation.

of two horses, four cows, eighteen sheep, and a sow. Each year the family was required

to submit ten percent of their produce to their landlord, Stift Levern, and to provide

transportation to its storehouses. They also owed annual obligations to three separate

civil authorities, Amt Rahden, Amt Levern, and Amt Lemförde. In total, these civil

obligations consisted of another tenth of the produce of their farm, plus several

sheep and hens, a moderate amount of cash, and about ten days of compulsory labor

on roads, public buildings, and transportation.

The two new family farms, established just a few years before the census, were much smaller. Oppenwehe 47, headed by Thomas’s brother Heinrich, had about four acres, plus access to common grazing land, which was a substantial benefit. Livestock consisted of just two cows. Like their relatives at Oppenwehe 3, they provided ten percent of their crop to Stift Levern and another ten percent to the civil authorities. Other obligations were proportionally smaller, and they were evidently not required to provide personal labor, possibly because they lacked the horses that were often required. The farm at Oppenwehe 50, headed by Thomas’s brother Gerd Heinrich, was even smaller, at about two acres, plus grazing rights. As at number 47, livestock consisted of two cows, and obligations the landlord and civil authorities were similar. Interestingly, both of these small farms were also required to provide a skein of yarn yearly to the sexton of Wehdem Parish, of which Oppenwehe was a part.

LIFE IN A NORTH GERMAN VILLAGE

In 1700 the economy of a typical north German village was based nearly entirely on

peasant families engaged in subsistence farming. Each household, usually consisting

of three generations living in common, was  expected to maintain itself on the produce

of its own fields, with enough surplus to meet the relatively moderate exactions

of the landlord and the civil authorities. Because a certain minimum amount of land

was required to meet these demands for a family, it was in the interest of all that

the number of families and households be maintained at a fairly stable level, once

all available land had been occupied.

expected to maintain itself on the produce

of its own fields, with enough surplus to meet the relatively moderate exactions

of the landlord and the civil authorities. Because a certain minimum amount of land

was required to meet these demands for a family, it was in the interest of all that

the number of families and households be maintained at a fairly stable level, once

all available land had been occupied.

In most of northern Germany, population stability was maintained through indivisibility

of farms and limitations on family formation. In each generation, one offspring was

selected to inherit the entire family farm, which was transferred to his or her possession

at the time of marriage. A detailed marriage contract formalized the transfer, contained

guarantees for lifelong maintenance of the retiring parents, and granted a small

living bequest to all other offspring. Ideally, the non-

Occasionally landless men and women were allowed to marry and live as renters and

day-

During periods of population growth, however, there was considerable pressure to

find sufficient land to support additional families. During the 15th and 16th centuries,

as the population recovered from the plagues of the preceding period, new families,

called Markkötter, were gradually accommodated on smaller plots of land, despite

the objections of the older established families, who opposed the increased demands

on common grazing land. Then, in the 16th century, it became necessary to settle

additional new families, often headed by retired soldiers who had been promised land,

on small plots actually carved from the village common and pieced together from inferior

sections; the status of these families is reflected in the term applied to them:

Brinksitzer, literally “brink-

As the area was populated, a distinct hierarchy emerged among the peasant families.

At the top were the long-

As the area was populated, a distinct hierarchy emerged among the peasant families.

At the top were the long-

The remarkable stability and conservatism of the social structure is exemplified by the history of the four established Priesmeyer farms in Oppenwehe. During the five generations between 1680 and 1820, each of the farm families had an average of six children per generation, of whom an average of four survived to adulthood. Of these four, one in each generation was chosen to inherit the family farm, and the other three were married to heirs of other substantial farms in Oppenwehe or nearby villages. Virtually no one left the immediate area, and no one fell out of the landholding class, with one exception, the line that led to the El Campo and Moulton branch, which we’ll examine later.

At the very bottom of the social hierarchy were those without any land - or Häusling (house-

or Häusling (house-

It is important to emphasize that most land-

The peasant’s relationship to his landlord was thus basically feudal, a relic of the Middle Ages. But it was very far from the lord and serf relationship that characterized the large noble estates of East Prussia and Russia. By 1700 in northwest Germany, the landlord was seldom present in the village and often lived at a considerable distance. At least a part of the annual tithe had been converted from a portion of farm produce to a cash payment. It is evident from the documentary record that very few families were ever evicted from their land. In general, the relationship of “dependence” on a landlord was considered desirable. It conferred substantial security and stability of living conditions as well as significant status in the community.

Apart from the landlord, peasant families dealt with a small nucleus of authority

figures. The local Amtshaus -

Apart from the landlord, peasant families dealt with a small nucleus of authority

figures. The local Amtshaus -

It should not be imagined, however, that life was idyllic. Variable weather caused periodic famines, and once every twenty years or so an epidemic of smallpox or dysentery wiped out a large portion of the children and vulnerable old people. Tuberculosis and other bronchial disorders were the scourge of everyone. Medicine was primitive at best, and chronic disabilities were widespread. While midwives were usually quite effective in managing routine pregnancies, a significant number of women died in childbirth. The wooden structures of the village, many of them roofed with thatch, were notoriously vulnerable to fire, and large sections of the village were periodically destroyed in conflagrations.

One feature of peasant culture must be understood as we learn about the Priesmeyers,

and this is the impact of inheritance on naming practices. In pre-

Because the undivided farm was so important to the family through succeeding generations,

the surname assumed by the new generation was that of the heir; if this was a daughter,

her bridegroom assumed her surname, and thus it was passed on to their offspring.

He retained her surname even if she died and he remarried, since it was the name

of the farm, which he still held. Likewise, the widow of a male heir would confer

the surname associated with the farm on her new husband, if she remarried. Finally,

if a farm fell vacant because there was no suitable heir in a particular generation,

the family chosen to take over the farm would adopt the surname associated with the

farm. This custom produces, to the untrained eye, a peculiar-

The population of Oppenwehe and the surrounding area remained relatively stable for the first half of the 18th century. Natural population growth was constrained by periodic epidemics of smallpox and, especially, of dysentery, with two major outbreaks, in 1719 and 1748. But then a steady upward trend began, facilitated by two significant developments: the introduction of smallpox inoculation and the acceptance of the potato as a worthy substitute for bread. The abatement of smallpox naturally enabled a larger proportion of children to survive to adulthood, and the potato, which was roughly five times more nutritionally productive per acre than grains, provided the food to keep the growing population alive.

Still, limited resources, especially land, would have kept a brake on household formation

by restraining  permissions to marry. But a simultaneous development during this period

opened the way for families without land to earn enough to support themselves. This

was the rapidly growing worldwide market for German linen. Peasant families working

in their own homes found that they could spin and weave locally grown flax into high

quality fabric that was in great demand, especially in France and in the expanding

colonies in the Americas. Local markets (Legge) were established that enabled families

to bring their linen for sale and receive compensation in cash. Simultaneously, this

infusion of cash into the economy in general also promoted growth.

permissions to marry. But a simultaneous development during this period

opened the way for families without land to earn enough to support themselves. This

was the rapidly growing worldwide market for German linen. Peasant families working

in their own homes found that they could spin and weave locally grown flax into high

quality fabric that was in great demand, especially in France and in the expanding

colonies in the Americas. Local markets (Legge) were established that enabled families

to bring their linen for sale and receive compensation in cash. Simultaneously, this

infusion of cash into the economy in general also promoted growth.

These three factors -

Then, in the late 1840s, a series of poor harvests placed increasing pressure on everyone. Finally, in 1851, after the opening of the railway from Minden to Cologne, a large mechanized linen spinning mill was constructed in the nearby town of Bielefeld, and the bottom fell out of the market. Landless families who had barely survived by spinning and weaving were driven to the wall.

THE GREAT 19TH CENTURY EMIGRATION

Faced with troubling changes in their environment and dwindling economic resources,

landless peasants throughout Germany began to seek opportunity elsewhere. Those who

lived close to growing cities migrated there and took jobs in the new manufacturing

industries. But those in more isolated areas, like Oppenwehe, began to look abroad

and especially to America. Even the poorest were literate, having been taught to

read in the parish schools, which they had been required to attend until age fourteen.

They read glowing accounts of the New World, such as those of the widely-

The great fertility of the soil, its immense area, the mild climate, the splendid

river connections, the completely unhindered communication in an area of several

thousand miles, the perfect safety of person and property, together with very low

taxes -

Duden thus captured the contrast between life in Germany, where land was expensive (and sometimes unobtainable at any price) and wages were low, and life in America, where land was abundant and inexpensive and labor was in demand. Simultaneously, local and state governments in America, seeking to attract industrious settlers on the expanding frontier, published brochures and commissioned recruiters in Germany. Merchants, who were then importing cotton and other raw materials from America and sending ships back only partly loaded, learned that they could fill their holds with emigrants by offering attractive fares. When the seaports of northern Germany, particularly Hamburg and Bremen, observed the prosperity that was accruing to the French and Dutch ports as they served transiting emigrants, they moved quickly to invest in infrastructure and dispatched agents to encourage departing families to choose them for their voyage.

During the nineteenth century, nearly five million Germans came to live in America.

After 1845 yearly totals usually exceeded 100,000, except for the years of the U.S.

Civil War. Both individuals and families came, and with rare exceptions their motives

were entirely economic: to escape the dwindling opportunities in their homeland to

earn their share of the prosperity of the growing nation. They were usually not entirely

destitute but rather had carefully husbanded their resources in Germany and came

with enough money to get started, whether in a town or on a farm. In general, they

were devoted to family and community, calmly religious, frugal, industrious, and

reasonably well educated. Their goals were markedly conservative: they hoped to recreate

the world that they believed that their grandparents had enjoyed -

This is the classic story of the great German immigration to America in the nineteenth century. As we will see in the following section, it describes an important portion of the Priesmeyers, primarily those who settled in Texas. But the majority of the Priesmeyer immigrants were evidently moved by a somewhat different set of considerations. While they too sought the comparative benefits of the expanding American economy, they were not drawn to the conservative vision of a life devoted to the rural environment and farming. Instead, they chose to settle in the rapidly growing cities of the Midwest, primarily St. Louis. Their goal was not to accumulate the resources to purchase a farm but rather to explore their opportunities in the urban environment, first as craftsmen and laborers and then as investors in their own businesses. While they remained conservative in their devotion to family, religion, and community, their economic outlook was distinctly progressive.

While we cannot know for certain why so many Priesmeyer immigrants chose to settle

and work in cities, one key factor in their background may explain most of their

motivation. As we will see below, the dominant figure in the development of the branch

of Oppenwehe 47 -

It is quite likely that Johann Friedrich’s descendants were influenced by his example

and may have been attracted to commerce by their involvement in the family businesses.

Most important, it is evident that Johann Friedrich began a family custom of requiring

his non-

Twenty male descendants of Johann Friedrich Priesmeyer emigrated to America between 1848 and 1923, nineteen of whom lived long enough to establish themselves in their occupations. Twelve settled in or near St. Louis, three in Cleveland, two in Chicago, one in Fort Wayne, and one in Garwood, Texas (after settling initially in St. Louis). Only one took up farming, near St. Louis. The others, having typically begun as common laborers, ultimately established themselves as manufacturers, wholesalers, merchants, grocers, and retailers. Several amassed considerable wealth and became pillars of the community.

St. Louis held a special attraction for these industrious immigrants. Drawn by the commentary of Gottfried Duden in the 1820s, as noted above, Germans flocked to the growing city. With just 25,000 inhabitants in 1840, it tripled in population over the next ten years; half of the increase consisted of German immigrants. As noted by historian Walter Kamphoefner,

Since mid-

As the following family stories reveal, the immigrants who settled in St. Louis and other cities acclimatized and modernized rapidly, while their farming cousins in Texas remained true to rural traditions and values for at least another generation if not more. Most notably, the urban Priesmeyers had fewer children, who resided longer with their parents, married late, and themselves had small families. They often gave their children anglicized names and were willing to explore their options in the diverse religious environment of their new country. By contrast, the rural Priesmeyers married early and had large numbers of children, whom they gave traditional German names. They normally remained faithful to their Lutheran faith for several generations unless they married someone of a different religion, especially a Roman Catholic.

Consequently, while the branch of Oppenwehe 47 provided more than half of the male

immigrants, who quickly urbanized, their descendants today make up a relatively small

part of the Priesmeyers living in America. Instead, well over half of today’s Priesmeyers

descend from just two young brothers, born in poverty a few miles from Oppenwehe,

who settled in east Texas (El Campo and Moulton) in 1860 and took up farming. Although

they too were descendants of Oppenwehe 47, their line had broken away 150 years earlier

and had become landless and poor. By the time the two branches -

PRIESMEYER IMMIGRANTS TO AMERICA

The following sections explore the fortunes of the various immigrant Priesmeyer branches. You may wish to skip ahead to your own branch, but it is hoped that you will also enjoy reading about the experiences of your cousins in the other branches. Because the narrative may be difficult to follow, especially if you are seeking your own ancestor, two summary aids have been prepared. The first is a list of all 46 immigrants in the order of their year of departure from Germany, with their dates and locations of birth, marriage, and death. Particularly helpful may be the entry immediately after the full German name that gives the name that the immigrant used in America, which was often anglicized. The second aid is a summary chart of the various Priesmeyer branches and their ultimate destinations in America. Please contact the author if you need assistance.

The Priesmeyers of Oppenwehe 47: the Midwest, and Garwood, Texas

The first generation on the new farm at Oppenwehe 47 exemplified the struggles of the family as they established themselves. Heinrich Priesmeyer and his wife Anne Alheit Hilmer, who married in 1665, began with a very small plot, as we saw above in Thomas Priesmeyer’s 1662 marriage addendum. Yet they laid a solid foundation for future generations by adding steadily to their holdings. Their primary task was to ensure a successful transition to the next generation, and they chose their oldest son, Johann Heinrich, born in 1668, to be their heir. He took over the farm at the time of his marriage, in 1692, to Catharine Elisabeth Battenhorn of Rahden, permitting his parents to retire to a cottage near the family home.

Or at least that was the plan. As it turned out, the erstwhile retirees were not happy with their son and his new wife. In November 1692 they submitted an agreement to their landlord in Levern:

Whereas Heinrich Priesmeyer of Oppenwehe and his wife Anne Alheit [Hilmer] recently handed over their small farm to their son Johann Heinrich and his wife Catharine Elisabeth Battenhorn, but they now find that they cannot reconcile and agree with them, they have today reserved for themselves the following instead of retiring:

1. The rye field to the west of the house;

2. A cabbage patch in the garden in Martin Holle’s field;

3. An average-

4. A breeding goose, which, along with the cow, the young couple will feed and care for;

5. ____ The great kettle to be reserved for their use as often as it might be needed, without any objection or impediment;

6. It is agreed and decided that the other two sons and three daughters, rather than

awaiting their inheritance, will each immediately have fifteen talers, a half-

Everyone was satisfied with this agreement and promised to live in peace and harmony.

As can be seen from this document, the parents did as much as they could for their

other five marriageable children. While they were all eventually married to farm

heirs -

The next generation at Oppenwehe 47, led, as we saw above, by heir Johann Heinrich

Priesmeyer, born in 1668, continued the development of the farm, but finding spouses

for the children remained a challenge. Apart from the heir, Johann Hermann, born

in 1697, the other three surviving children married to small farms at a relatively

advanced age. Then, with Johann Hermann’s generation, misfortune befell the line.

He took over the farm in 1723, at the time of his marriage, but he lived barely five

more years, leaving his widow and a daughter, Marie Catharine, born in 1729 after

his death, who became by default the eventual heir to the farm. In 1753 Marie Catharine

married Hermann Heinrich Marcus of Oppenwehe 46, and they took over the farm at that

time. In accordance with regional custom, Hermann Heinrich assumed the Priesmeyer

surname, and thus it was passed on to their descendants. It is evident that the farm

prospered under their management; their three surviving children all married well,

including their chosen heir, Johann Friedrich, born in 1764.

The next generation at Oppenwehe 47, led, as we saw above, by heir Johann Heinrich

Priesmeyer, born in 1668, continued the development of the farm, but finding spouses

for the children remained a challenge. Apart from the heir, Johann Hermann, born

in 1697, the other three surviving children married to small farms at a relatively

advanced age. Then, with Johann Hermann’s generation, misfortune befell the line.

He took over the farm in 1723, at the time of his marriage, but he lived barely five

more years, leaving his widow and a daughter, Marie Catharine, born in 1729 after

his death, who became by default the eventual heir to the farm. In 1753 Marie Catharine

married Hermann Heinrich Marcus of Oppenwehe 46, and they took over the farm at that

time. In accordance with regional custom, Hermann Heinrich assumed the Priesmeyer

surname, and thus it was passed on to their descendants. It is evident that the farm

prospered under their management; their three surviving children all married well,

including their chosen heir, Johann Friedrich, born in 1764.

Johann Friedrich Priesmeyer began a new and impressive era in the history of Oppenwehe

47. At the time of his marriage in 1789, he was a soldier, in the 2nd battalion of

the Prussian Royal Grenadier Guard in Potsdam. After military service, he returned

to Oppenwehe and assumed control of the family farm. In addition to increasing his

landholdings, he established an inn and tavern, which became the center of community

life in Oppenwehe. We can be certain that his wife, Marie Elisabeth Röhling of Oppenwehe

29, was just as remarkable, having supported his endeavors while giving birth to

ten children, including a set of triplets and a set of twins. (Unfortunately, the

churchbook says relatively little about the women of the parish.) When Johann Friedrich

died, in 1835, the pastor noted prominently in the churchbook that Johann Friedrich

had been a “churchwarden, businessman, and farm holder.” Most important for our story,

twenty-

The next generation was headed by Johann Friedrich’s and Marie Elisabeth’s son, Christian

Friedrich, born in 1801. With his generation, conditions had begun to change rapidly

in the region. Land reforms were leading to consolidation of peasant farms and enclosure

of common pasturage, undermining the traditional structures of subsistence farming

and reducing the amount of available land for new farms. But the population continued

to grow, and opportunities to establish traditional landholding marriages and households

steadily diminished. While Christian Friedrich was able to provide the well-

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1825

Emigrated in 1848, probably to Cincinnati

Evidently died shortly after arrival in America

Johann Christoph Gottlieb Priesmeyer, born in 1827

Emigrated in 1848 to Cincinnati and settled in St. Louis

Occupation: bricklayer

Married Caroline Wilhelmine Henriette Spreen of Westrup in 1851

Child:

Heinrich Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1856 in St. Louis

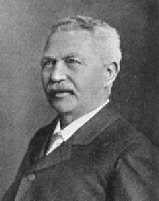

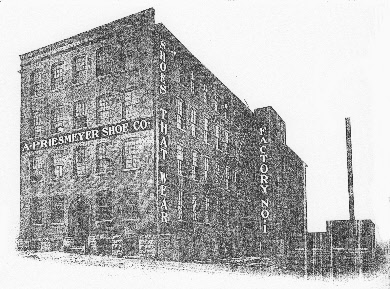

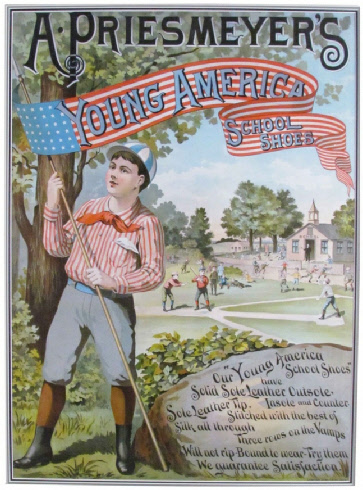

Heinrich Wilhelm August Priesmeyer, born in 1832

Heinrich Wilhelm August Priesmeyer, born in 1832

Emigrated in 1849 to Cincinnati and settled in St. Louis

Occupation: shoemaker, then major shoe manufacturer

Married Caroline Steinbrügge of Hannover in 1860

Child:

Edward Priesmeyer, born in 1867 in St. Louis (died in 1871)

Johann Friedrich Carl Priesmeyer, born in 1838

Emigrated in 1857 to St. Louis

Occupation: confectioner

Married Louise Steinbrügge of Hannover in 1865

Children:

Charles J. Priesmeyer, born in 1867 in St. Charles, Missouri

Alvina Priesmeyer, born in about 1868 in St. Charles, Missouri

August E. Priesmeyer, born in 1870 in St. Louis

Ida Priesmeyer, born in 1872 in St. Louis

Christian Friedrich’s brother, Johann Heinrich, born in 1790, married in 1818 and founded a small new farm in Oppenwehe, which was given the number 70. Three of his five surviving children emigrated to America:

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm August Priesmeyer, born in 1824

Emigrated in 1854 to St. Louis and settled in Chicago

Occupation: baker

Married Margarethe Wolf of Hesse Darmstadt in 1860

Children:

Edward August Gottlieb Priesmeyer, born in 1861 in St. Louis

Emma Priesmeyer, born in about 1866 in Chicago

Augusta Priesmeyer, born in 1870 in Chicago

Anna Priesmeyer, born in 1871 in Chicago

Albert A. Priesmeyer, born in 1873 in Chicago

Matilda Priesmeyer, born in 1877 in Chicago

Hattie Priesmeyer, born in about 1880 in Chicago

Dollie Priesmeyer, born in 1883 in Chicago

Doris B. Priesmeyer, born in about 1887 in Chicago

Heinrich Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1831

Emigrated in 1851 to St. Louis

Occupation: grocer, then chemical merchant

Married Anne Marie Gaus of Prussia in 1860

Children:

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1860 in St. Louis

Christian Julius Priesmeyer, born in 1863 in St. Louis

Matilda Anna Priesmeyer, born in 1865 in St. Louis

August Friedrich Gottlieb Priesmeyer, born in 1834

Emigrated in 1852 to St. Louis and settled in Chicago

Occupation: grocer, teamster, policeman, coal merchant

Married Christine Wolff of Hesse in 1860

Children:

August Gustave Priesmeyer, born in 1860 in St Louis

August Heinrich Priesmeyer, born in 1861 in Chicago

Johann Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1863 in Chicago

George Louis Priesmeyer, born in 1868 in Chicago

Mary Priesmeyer, born in 1869 in Chicago

Frank Adam Priesmeyer, born in 1872 in Chicago

Emma Priesmeyer, born in 1878 in Chicago

Charles Priesmeyer, born in about 1880 in Chicago

Emily H. Priesmeyer, born in about 1882 in Chicago

Lillian Priesmeyer, born in 1883 in Chicago

Another of Christian Friedrich’s brothers, Johann Christoph, born in 1796, founded a small new farm in the neighboring village of Oppendorf, which was given the number 107. Of his eight surviving children, five emigrated to America:

Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1821

Emigrated in 1848 to Cincinnati and settled in St. Louis

Occupation: bricklayer

Married Anne Marie Kicke of Westphalia in 1852

Children:

Heinrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1856 in St. Louis

Caroline Priesmeyer, born in about 1858 in St. Louis

Louise Charlotte Friederike Priesmeyer, born in 1826

Emigrated in 1846 to St. Louis

Married Johann Christoph Schumacher of Westrup in 1846

Marie Wilhelmine Caroline Priesmeyer, born in 1928

Emigrated in 1852 to St. Louis

Married Gerhard Heinrich Luke of Germany in 1853

Charlotte Wilhelmine Henriette Priesmeyer, born in 1830

Emigrated in 1847 to St. Louis and settled in Quincy, Illinois

Married Dietrich Schmidt of Germany in 1849 and then Franz Heinrich Wittler of Hannover in 1853

Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1835

Emigrated in 1852 to St. Louis

Occupation: farmhand, then laborer

Married Louisa Knepper of Hannover in 1868

Children:

Amalia Priesmeyer, born in about 1869 in St. Louis

Frederick W. Priesmeyer, born in 1873 in St. Louis

Yet another brother of Christoph Friedrich, Friedrich Wilhelm, born in 1798, acquired an existing farm at Oppendorf 99. Six of his eight surviving children emigrated to America:

Christoph Wilhelm August Priesmeyer, born in 1832

Emigrated in 1850 to St. Louis

Occupation: butcher

Married Elizabeth of Missouri in about 1854

Children:

Caroline Priesmeyer, born in about 1855 in St. Louis

William H. Priesmeyer, born in 1859 in St. Louis

Lena Priesmeyer, born in about 1863 in St. Louis

Henry E. Priesmeyer, born in 1866 in St. Louis

Edward T. Priesmeyer, born in 1874 in St. Louis

Henriette Wilhelmine Caroline Priesmeyer, born in 1838

Emigrated in 1859 and settled in Staunton, Illinois

Married Wilhelm Meyer of Braunschweig in 1862

Christoph Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1842

Emigrated in 1867 and settled in Madison County, Illinois

Occupation: farmer

Married Sophia Bartmann of Prussia in 1874

Children:

Henriette Louise Caroline Priesmeyer, born in 1875 in Staunton, Illinois

Anne Christine Caroline Priesmeyer, born in 1878 in Staunton, Illinois

Ernst Carl William Priesmeyer, born in 1880 in Madison County, Illinois

Fredericka Priesmeyer, born in 1882 in Madison County, Illinois

Mathilda Sophia Priesmeyer, born in 1883 in Madison County, Illinois

Lydia Priesmeyer, born in 1887 in Madison County, Illinois

Frederick Priesmeyer, born in 1895 in Madison County, Illinois

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1844

Emigrated in 1866 to St. Louis

Occupation: coal merchant

Married Christine Schumacher of Westphalia in 1874

Children:

Anne Henriette Priesmeyer, born in 1874 in St. Louis

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1876 in St. Louis

Mathilde Wilhelmine Caroline Priesmeyer, born in 1878 in St. Louis

Caroline Priesmeyer, born in 1881 in St. Louis

Charles S. Priesmeyer, born in 1884 in St. Louis

Henriette Wilhelmine Caroline Priesmeyer, born in 1845

Emigrated in 1860 and settled in Staunton, Illinois

Married Heinrich Wilhelm Hiffmann of Westphalia in 1864

Eight children

Heinrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1847

Emigrated in 1866 to St Louis

Occupation: chemical merchant

Married Anne Marie Gaus (widow of his cousin Heinrich Friedrich Priesmeyer) in 1872

Child:

Frederick W. Priesmeyer, born in about 1872 in St. Louis

In summary, from the pivotal household of Johann Friedrich Priesmeyer and Marie Elisabeth

Röhling at Oppenwehe 47, eighteen grandchildren emigrated to America between 1846

and 1866 -

Continuing on to the following generations of the main-

Continuing on to the following generations of the main-

Carl Christian Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1854

Emigrated in 1872 to St. Louis and eventually settled in Indianapolis

Occupation: shoe salesman, then bookkeeper

Married Clotilde Zuendt of Wisconsin in 1881

Children:

Irma Jeanette Priesmeyer, born in 1882 in Missouri

Venita C. Priesmeyer, born in 1884 in Jefferson City, Missouri

Alice Priesmeyer, Born in 1887 in St. Louis

Jeanette Mildred Priesmeyer, born in 1889 in Missouri

William Albert Priesmeyer, born in 1892 in Missouri

Another of Bernhard Heinrich Wilhelm’s brothers, Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1856, married Henriette Wilhelmine Caroline Schröder, heir to her family’s farm at Oppendorf 21. Four of their five surviving children emigrated to America:

Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1878

Emigrated in 1893 to Fort Wayne, Indiana, and eventually settled in Texas

Occupation: laborer, then real estate agent

Married Emma Helen Weimar of Dashwood, Ontario, in 1909

Children:

Carl W. Priesmeyer, born in 1910 in Allen County, Indiana

William Weimar Priesmeyer, born in 1912 in Rock Island, Texas

Cordelia Priesmeyer, born in 1916 in San Antonio, Texas

Henriette Caroline Wilhelmine Priesmeyer, born in 1883

Emigrated in 1905 to Bangor, Pennsylvania; then to Rock Island, Texas; and eventually settled in Norwalk, California

Married John M. Bender in about 1908

Without children

Heinrich Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1885

Emigrated in 1901 to St. Louis and settled in Garwood, Texas

Occupation: shoe salesman, then proprietor of a chain of general stores

Married Clara Marie Beck in 1910

Children:

Edward William Priesmeyer, born in 1911 in Rock Island, Texas

Alice Wilhelmina Anna Priesmeyer, born in 1913 in Yoakum, Texas

Frederick Beck Priesmeyer, born in 1921 in Garwood, Texas

William Xavier Priesmeyer, born in 1922 in Garwood, Texas

Wilhelmine Louise Priesmeyer, born in 1897

Emigrated in 1923 to Houston, Texas

Married Henry A. Schade in 1928

Along another line originating at Oppenwehe 47, we have already seen above that Johann Christoph Priesmeyer, born in 1796, established a new farm at Oppendorf 107 and sent five children to America. His son Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1824, inherited the farm in 1848. From his three marriages, three children emigrated to America:

Christoph Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1849

Emigrated in 1864 to Cleveland

Occupation: grocer

Married Rosina Hermann of Bavaria in 1875

Without children

August Christoph Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1865

Emigrated in 1881 to Cleveland

Occupation: butcher and grocer

Married Wilhelmine Huy of Cleveland in 1889

Children:

Irene M. Priesmeyer, born in 1892 in Cleveland

Walter C. Priesmeyer, born in 1894 in Cleveland

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1868

Emigrated in 1882 to Cleveland and eventually settled in Randolph County, Missouri

Occupation: pharmacist

Married Bee Elliott of Missouri in 1896

Child:

Friederika Priesmeyer, born in Missouri in 1901

In the next generation at Oppendorf 107, the heir, August Friedrich Wilhelm, born in 1873, sent one child to America, who was the last of all the Priesmeyer emigrants:

Carl Theodor Priesmeyer, born in 1905

Emigrated in 1923 to Cleveland

Occupation: salesman, then branch manager for a beer importer

Married Dorothy Esther Zielke of Cleveland in 1931

Children:

Ellen Louise Priesmeyer, born in about 1937 in Cleveland

Carla Priesmeyer, born in 1939 in Cleveland

Today the main Priesmeyer lineage of Oppenwehe 47/Oppendorf 97 (modern address Oppendorfer

Strasse 1) -

Yet the descendants of this main branch do not today comprise the largest group of Priesmeyers in America. That distinction is held by the branch (also originating at Oppenwehe 47) that we will consider next, that of El Campo and Moulton, Texas. This branch sent only two emigrant brothers to America, in 1860, yet today its descendants substantially outnumber those of the Midwest branch. Why? Because most of the 27 immigrants of the main Oppenwehe 47 branch settled in cities and urbanized quickly. They had small families, and their children married late and also had small families. By contrast, the El Campo and Moulton immigrants were struggling farmers who married early and had large families, as did their children and grandchildren.

The Priesmeyers of Oppenwehe 47: El Campo and Moulton, Texas

The most numerous of the Priesmeyer branches in America today also has the most distinctive

history. It was the earliest lineage -

We have already seen that Heinrich Priesmeyer and Anne Alheit Hilmer founded a new

farm at Oppenwehe 47 in 1665 and that they selected their oldest son, Johann Heinrich,

born in 1668, to inherit the farm. Johann Heinrich’s younger brother, Gerd Heinrich,

born in 1670, was left with just a small endowment to facilitate his search for a

bride. Since he was not wealthy, he was undoubtedly fortunate to become engaged,

at the relatively advanced age of 34, to Agnese Platine Engelken, just 19 years old

and heir to her family’s small farm, number 44, in the nearby village of Levern.

So slight were his resources that his more fortunate brother Johann Heinrich paid

the required five taler fee to their landlord for his permission to marry, called

the Weinkauf.

younger brother, Gerd Heinrich,

born in 1670, was left with just a small endowment to facilitate his search for a

bride. Since he was not wealthy, he was undoubtedly fortunate to become engaged,

at the relatively advanced age of 34, to Agnese Platine Engelken, just 19 years old

and heir to her family’s small farm, number 44, in the nearby village of Levern.

So slight were his resources that his more fortunate brother Johann Heinrich paid

the required five taler fee to their landlord for his permission to marry, called

the Weinkauf.

In accordance with regional custom, Gerd Heinrich adopted the Engelken surname at

marriage, when he and his bride took possession of her farm. They had seven children

between 1708 and 1726, all of whom survived to adulthood. Ultimately they passed

their farm at Levern 44 to one of their older sons, Johann Heinrich, when he married

in 1733, and then applied themselves, as did all good land-

Most important for our history, they were unable to provide a sufficient endowment

to their son Christoph Friedrich, born in 1718.  He evidently moved in his teens to

the nearby village of Marl and worked as a day-

He evidently moved in his teens to

the nearby village of Marl and worked as a day-

Friedrich and Engel Priesmeyer (as they were called) established themselves in a

laborer’s cottage in nearby Dielingen Parish, first in the village of Haldem and

then at the Blumenhorst farm at Arrenkamp 13, finally settling at the Wellmann farm

at Arrenkamp 11. Here they undoubtedly worked as day-

Four of their seven children were daughters, and all four were in their 30s before

marrying landless laborers; more significant, among them they had a total of at least

five children out of wedlock before their marriages. We can be sure that their parents

were mortified by this behavior, but in the environment of rural 18th century Germany

they, as a family living in poverty, could do little to discourage or prevent it.

Their three sons were nearly as luckless as their daughters: only one succeeded in

marrying and having children -

Like his father, as a young man Johann Hermann Priesmeyer moved north to the nearby village of Marl, where he obtained work on the Fyhe farm, at Marl 7. At the age of nineteen he enlisted in the Hanoverian army and was a private in the 1st company, 2nd battalion, 2nd infantry regiment when, in June 1783, he was granted permission to leave the army. In 1779 he had married Anne Sophie Lucie Meyer of Marl, 24 years old and six weeks pregnant. (Interesting sidelight: Ms. Meyer provides, in her family tree, the earliest documented ancestor of all of the Priesmeyer branches: Eggert zum Mohr, born in about 1470 at Marl 6.) They had five children, only two of whom survived to adulthood.

In 1810 the older of the two children, Johann Friedrich, born in 1779, married Anne

Marie Lucie Luther of Marl, and they settled in a laborer’s cottage; initially they

had just one cow, one calf, two pigs, one gander, two geese, and no horses or beehives.

In 1811, however, they received a bit of good luck: they were invited  to take over

the farm of the Buck family (1st cousins of Johann Friedrich’s wife) at number 18

in the neighboring village of Quernheim. Unfortunately, the farm was in bad condition,

and they had to invest nearly 500 talers to restore the “dilapidated” house and to

return the land to productivity. Here they had six children, four of whom survived

to adulthood. Although they had a farm of their own, it was so small that they continued

to work as day-

to take over

the farm of the Buck family (1st cousins of Johann Friedrich’s wife) at number 18

in the neighboring village of Quernheim. Unfortunately, the farm was in bad condition,

and they had to invest nearly 500 talers to restore the “dilapidated” house and to

return the land to productivity. Here they had six children, four of whom survived

to adulthood. Although they had a farm of their own, it was so small that they continued

to work as day-

Nevertheless it is evident that the industriousness of the family enabled them gradually to build their farm at Quernheim 18. As their heir, Johann Friedrich and Anne Marie Lucie chose the younger of their two sons, Johann Friedrich, born in 1822, who continued to build the farm and in about 1875 passed it on to his heir. A map of 1870 shows that by that year several large plots of land had been added to the original holdings.

Their older son, Heinrich Georg Ludwig Priesmeyer, born in 1815, became a day- next nineteen years in a laborer’s cottage on the property

of the Nobbe family at Quernheim 5. By a stroke of good fortune, a photograph of

this cottage was taken in about 1960, just before it was torn down, and the photograph

has survived. It shows a thatched Fachwerk (half-

next nineteen years in a laborer’s cottage on the property

of the Nobbe family at Quernheim 5. By a stroke of good fortune, a photograph of

this cottage was taken in about 1960, just before it was torn down, and the photograph

has survived. It shows a thatched Fachwerk (half-

In this cottage, Heinrich and Sophie had two sons, Hermann Friedrich Heinrich, born in 1842, and Heinrich Hermann Friedrich, born in 1845. The parents worked hard to make ends meet, often in difficult economic times; they worked in the fields and probably also spun and wove linen in their small home. Their sons attended school, and we know from their report cards that Heinrich was the better student (good in bible studies, very good in reading and writing).

By the early 1850s, however, after several bad harvests and the collapse of the market for handwoven linen, they were finding it progressively harder to survive. While they could have persisted and scraped by, as did many of their peers, they began to consider the possibility of going to America. Their interest was whetted by letters sent from recent emigrants from their area describing the opportunities in the United States. Most important, two of Sophie’s younger sisters, Charlotte and Louise, had already emigrated to Frelsburg, Texas, where they had married and established prosperous households. They undoubtedly wrote encouraging letters to Sophie, which evidently settled the matter.

As soon as son Heinrich was confirmed, in 1860, the family gathered together their

possessions and departed for America. Because Heinrich was considered a potential

inductee into the Hanoverian army and therefore normally prohibited from emigrating,

their pastor prepared a transcript of his baptism record that declared  that he was

three years younger than his actual age, enabling the family to slip past government

officials.

that he was

three years younger than his actual age, enabling the family to slip past government

officials.

On September 20, 1860, the family of four boarded the brig “Weser” in Bremerhaven. They were accompanied by Henriette Köster, from the nearby village of Westrup, who would soon marry the older Priesmeyer son, Friedrich. They were also joined by their neighbors from Quernheim, Friedrich and Charlotte Meyer with their infant son Heinrich, who would eventually marry the Priesmeyers’ first grandchild, Sophie. After a nine week voyage they landed in Galveston, on November 23, and embarked on the arduous trek to Frelsburg, 130 miles to the west.

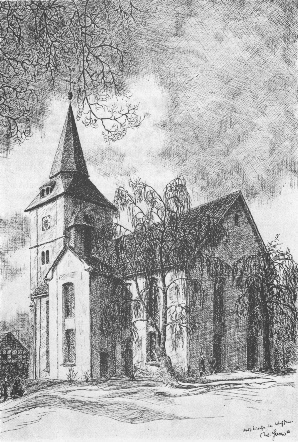

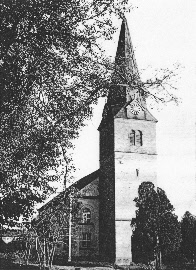

In 1860 Frelsburg was a prosperous German community that had been founded over twenty

years earlier. It already had several hundred inhabitants, a post office, two churches, two general stores, two blacksmiths, a cobbler, and a cotton gin. The photograph

reproduced here shows the main street in the 1800s, dominated by Trinity Lutheran

Church, where the Priesmeyers’ sons would eventually be married. It’s likely that

Sophie and the two boys reached Frelsburg by Christmas, but evidently Heinrich (the

father) died soon after arriving in Galveston and may never have seen the promised

land.

two general stores, two blacksmiths, a cobbler, and a cotton gin. The photograph

reproduced here shows the main street in the 1800s, dominated by Trinity Lutheran

Church, where the Priesmeyers’ sons would eventually be married. It’s likely that

Sophie and the two boys reached Frelsburg by Christmas, but evidently Heinrich (the

father) died soon after arriving in Galveston and may never have seen the promised

land.

The family arrived at a difficult time in America. Just five months later the forces of the Confederacy bombarded Fort Sumter, and the country was embroiled in four years of bitter civil war. While son Heinrich avoided conscription by the Confederate army, Friedrich was not so fortunate. In June 1863 he was drafted and assigned to Company H of the 17th Texas Infantry, at Camp Terry, in Austin. While he probably missed the battle of Milliken’s Bend in that month, a Union victory in which the 17th suffered 86 casualties, he evidently was with his unit campaigning in Louisiana the following November, when he was taken prisoner by Union forces. Declaring himself a deserter from the Confederate army, Friedrich then enlisted (perhaps not entirely voluntarily) in Company A of the 1st Regiment of the New Orleans Infantry of the U.S. Army, which was evidently assigned mainly to garrison and guard duty in New Orleans. At the end of the War, in 1865, like so many soldiers he simply left for home and later in life was absolved of all charges of desertion.

The two brothers established themselves in Texas:

Hermann Friedrich Heinrich Priesmeyer, born in 1842

Emigrated in 1860 to Frelsburg, Texas; later lived in Moulton, Texas

Occupation: farmer

Married Henriette Wilhelmine Caroline Köster of Westrup in 1861

Children:

Henrietta Sophia Dorothea Priesmeyer, born in 1862 in Frelsburg

Maria Adolphina Bertha Priesmeyer, born in 1867 in Frelsburg

Heinrich Gerhard Daniel Priesmeyer, born in 1869 in Frelsburg

Friedrich Ignatz Gerhard Priesmeyer, born in 1871 in Frelsburg

Henrietta Charlotta Meta Priesmeyer, born in 1874 in Frelsburg

Wilhelm Friedrich Karl Priesmeyer, born in 1876 in Frelsburg

Heinrich Johann Priesmeyer, born in 1878 in Flatonia

Ida Louise Katharina Priesmeyer, born in 1862 in Moulton

Heinrich Hermann Friedrich (Henry) Priesmeyer, born in 1845

Emigrated in 1860 to Frelsburg, Texas; children settled in El Campo, Texas

Occupation: farmer

Married Adolphine Gerhardine Sophie Becker in 1870

Children:

August Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1870 in Frelsburg

Theodore Gerhardt Priesmeyer, born in 1872 in Frelsburg

Meta Priesmeyer, born in 1874 in Fayette County

Louisa Maria Sophia Priesmeyer, born in 1877 in Fayette County

The two brothers worked as tenant farmers and struggled to support their families. The character of their lives is captured in an anecdote told by Friedrich’s granddaughter, Henrietta Meyer: “When Sophie [Friedrich’s daughter, born in 1862] was seven years old her dad was a Texas trail driver delivering flour. He had four horses pulling the wagon and two rest horses following. He was constantly having a high fever. Sophie would go along and bathe his head with cool river water.”

Both brothers died young and without significant wealth. Friedrich’s widow struggled to support her large family in Moulton. While she was able to purchase a small plot of land that she let to sharecroppers, it is evident that her resources always remained small. Heinrich’s widow married Frederick Lillie, in whose household her four children were raised. Many of the brothers’ children had large families, and today their descendants account for over half of all Priesmeyers in America, even though they were just two of the 46 Priesmeyer emigrants who came to America.

What about the branch of the family who stayed behind in Germany? It was initially headed by Johann Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1822, Heinrich Georg Ludwig’s younger brother, who was heir to the family farm at Quernheim 18. The farm was eventually passed to his grandson, Friedrich Heinrich Hermann, born in 1890. Heinrich excelled in schoolwork, finishing at the top of his elementary school class. By the time of his graduation, in 1905, his father and only sister were deceased, and his mother died soon thereafter, in 1906. Heinrich decided to sell the farm and study to become a teacher.

By 1934 Heinrich was the schoolmaster of the village of Holtensen and a staunch Nazi. In that year he published a long article about the rise of the Hitler Youth in his district. Here’s how he began:

“Young people! We are the soldiers of the future.

“Young people! Bearers of destiny.

“Hearts beat faster and the future is full of hope when we see our young boys marching, clad in brown and black. In sturdy hobnailed boots, a war chant on their lips, with their banners held high, they march in lockstep on forest paths and on broad highways. Determination inspires them, and they are driven to their goal. In every German province this is the scene. Young Germans are awake and ready to fulfill their profound duty now and forever.

“Under the great Nazi system, the Hitler Youth has set the ambitious goal of molding all of the boys and girls of Germany into a national movement, as the Führer wishes. The Hitler Youth proudly claims to be the one and only correct form of National Socialism for the young generation. It has thus assumed primary responsibility, with zeal and the will to fight, for the achievement of this great task, as set by the Führer himself.”

He then presented a lengthy narrative of the growth of the Hitler Youth, concluding:

“At the Party Convention in Hannover in 1934, 4,500 youth leaders from all of Lower Saxony, including boys and girls from our district, filled the huge rotunda of the city hall. They were aware of the significance of this event, forging the unbreakable unity of the youth of Lower Saxony. As the organ powerfully intoned variations on ‘Our Flag Waves above Us’ and as the chairmen spoke, everyone experienced the greatness made possible only by solidarity with the concept of the Führer. On the following day hundreds of thousands of these young people in every German province swore the Oath of Allegiance. Their dynamic strength will unite all of the youth of Germany in discipline and comradeship. The ring is almost closed, but the goal is not yet achieved. Yet our Hitler Youth know, as it says in their almanac: ‘When we are bold and steadfast, Germany will live forever. And that is our resolve.’”

The Priesmeyers of Oppenwehe 3: Brenham, Texas

We last encountered Thomas Priesmeyer above, in the section on the origins of the family at Oppenwehe 3. He was the heir to the farm in 1662, when he married Marie Meyer of Oppenwehe 1. After her death in 1664, he married Anne Dorothee Grötemeyer of nearby Niedermehnen 24. Their son, Gerd Heinrich, born in 1672, inherited the farm at the time of his marriage, in about 1701, to Anne Margarethe Roemeyer of Oppenwehe 23.

Three generations later, a great grandson of Gerd Heinrich and Anne Margarethe, Berend Heinrich Priesmeyer, born in 1756, married Marie Catharine Hohlt of Wehdem 45 in 1780 and inherited the farm. After her death in 1807, he married Anne Marie Charlotte Hilmer of Oppendorf 41. A son of the second marriage, Johann Heinrich, born in 1810, married Marie Elisabeth Schmidt of Wehdem 87; one of their children eventually emigrated to America:

Charlotte Caroline Wilhelmine Priesmeyer, born in 1850

Emigrated in about 1872 and settled near Brenham, Texas

Married Johann Lehmann of Janovitz, Posen, in 1873

Another son of the second marriage, Johann Friedrich, born in 1820, married Wilhelmine Henriette Hagemeyer of Wehdem 34, with whom he had six children. In 1867, after he and five of their children had died, Henriette departed for America with her remaining child:

Heinrich Friedrich Christoph Priesmeyer, born in 1853

Emigrated in 1863 and settled near Brenham, Texas

Occupation: farmer

Married Charlotte Friederike Henriette Hüsemann of Oppenwehe in 1880

Children:

Louis Priesmeyer, born in 1882 near Brenham

Wilhelmina Priesmeyer, born in 1884 near Brenham

He then married Caroline Wilhelmine Henriette Kalkhake of Wehdem in 1887

Children:

Henry Priesmeyer, born in 1888 near Brenham

Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1890 near Brenham

Lydia Priesmeyer, born in 1892 near Brenham

Elizabeth D. Priesmeyer, born in 1896 near Brenham

Walter Priesmeyer, born in 1899 near Brenham

Meta Hulda Priesmeyer, born in 1904 near Brenham

George Otto Priesmeyer, born in 1907 near Brenham

A daughter of the first marriage of Berend Heinrich Priesmeyer, with Marie Catharine

Hohlt, Sophie Henriette, born in 1791, was eventually chosen to inherit the farm,

which she did in 1815, when she married Wilhelm Heinrich Engelbrecht of Westrup.

Following the traditional custom in the area, Wilhelm Heinrich should then have adopted

the Priesmeyer surname, but evidently because he was a descendant of a distinguished

line of schoolmasters, he retained his own surname and thus passed it on to his descendants.

One of their sons, Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Engelbrecht, born in 1829, married Marie Charlotte

Menke of Oppenwehe; they emigrated with their children in 1869 and settled near Brenham,

Texas. One of their grandsons, Heinrich Wilhelm Engelbrecht, born in 1843, emigrated

to the Brenham area in 1860 and married Henriette Friederike Wilhelmine Winkelmann

of Oppendorf; they eventually settled in Crawford, Texas. Both of these immigrants

would have been surnamed Priesmeyer if the old naming customs had been applied in

1815 to the marriage of Sophie Henriette Priesmeyer and Wilhelm Heinrich Engelbrecht.

born in 1829, married Marie Charlotte

Menke of Oppenwehe; they emigrated with their children in 1869 and settled near Brenham,

Texas. One of their grandsons, Heinrich Wilhelm Engelbrecht, born in 1843, emigrated

to the Brenham area in 1860 and married Henriette Friederike Wilhelmine Winkelmann

of Oppendorf; they eventually settled in Crawford, Texas. Both of these immigrants

would have been surnamed Priesmeyer if the old naming customs had been applied in

1815 to the marriage of Sophie Henriette Priesmeyer and Wilhelm Heinrich Engelbrecht.

Today Oppenwehe 3, the original Priesmeyer farm, with the modern address of Oppenweher Strasse 9, is occupied by Herbert Engelbrecht, 9th great grandson of the earliest documented Priesmeyer on record, Heinrich, born in about 1570. The farm has thus been in continuous occupation by the Priesmeyer/Engelbrecht family for nearly 450 years, through twelve generations.

The Priesmeyers of Oppenwehe 50: Cincinnati and New York

We saw above that Gerd Heinrich Priesmeyer took over the new farm created for him

by his parents in 1670, at the time that he married Margarethe auf dem Holze of Oppenwehe

21. Thus began five long-

A child of the fifth generation, Johann Heinrich Priesmeyer, born in 1792, married Margarethe Charlotte Bosse, who was the widow of the heir to the Lammert farm at Oppenwehe 18. Johann Heinrich thus became holder of the Lammert farm, although he retained his own surname, since by that time the old naming custom had changed. Two of his sons emigrated to America:

Christian Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1828

Emigrated in 1853 and evidently died soon after arrival

Johann Heinrich Priesmeyer, born in 1830

Emigrated in 1850 and settled in Brooklyn, New York

Occupation: laborer, then grocer

Married Anne of Prussia in about 1851.

Children:

George H. Priesmeyer, born in about 1852 in New York

Emma Priesmeyer, born in about 1864 in New York

Dora Priesmeyer, born in about 1866 in New York

John L. Priesmeyer, born in 1868 in New York

Another of his sons, Christian Friedrich Wilhelm, born in 1832, was unable to find the heir to a farm to marry, so he married a laborer’s daughter and became a laborer himself. He had two sons before his untimely death at the age of 32; both of them ultimately emigrated:

Berend Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1861

Emigrated in 1903 to Cincinnati

Occupation: laborer

Married Henriette Charlotte Caroline Weggehöft of Oppenwehe 71 in 1889

Children:

Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1889 at Oppenwehe by 50

Wilhelm Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1891 at Oppenwehe by 50

Wilhelmine Henriette Priesmeyer, born in 1898 at Oppenwehe 66

Wilhelmine Henriette Caroline Priesmeyer, born in 1900 at Oppenwehe 66

Caroline Priesmeyer, born in 1903 at Oppenwehe 66

Harry Priesmeyer, born in 1905 in Ohio

Luella Priesmeyer, born in about 1908 in Ohio

Albert Priesmeyer, born in about 1912 in Ohio

Johann Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in 1864

Emigrated in 1880 to Cincinnati

Occupation: gardener

Married Elizabeth Schulte of Ohio in 1888

Children:

Frederick Henry Priesmeyer, born in 1889 in Ohio

Louis William Priesmeyer, born in 1892 in Ohio

Minnie Priesmeyer, born in 1897 in Ohio

One more immigrant came from the line of Oppenwehe 50, but she was not genealogically a Priesmeyer. She descended from Johann Friedrich Bockhorn, who took over the Priesmeyer farm and assumed the surname in 1799 at the death of the father of the above Johann Heinrich Priesmeyer, born in 1792. Since Johann Heinrich’s brother, the heir in that generation, was childless, the farm eventually passed to a grandson of Bockhorn, one of whose children emigrated:

Marie Charlotte Henriette Priesmeyer, born in 1865

Emigrated in 1883, arriving in Baltimore

Ultimate outcome unknown

The Priesmeyers of Oppenwehe 53: Taylor, Texas

We have already seen the expansion of the original Priesmeyer domains in 1662, when Heinrich Mundt and Catharine Priesmeyer divided the old Priesmeyer estate at Oppenwehe 3 into three farms, making provision for each of their sons, Thomas, Heinrich, and Gerd Heinrich. But there was still one more farm to come.

Thomas Priesmeyer’s oldest son, Martin, born in 1664, was not chosen as heir to his

father’s farm at Oppenwehe 3, so he followed an alternate and distinctive path to

prosperity. At the age of eighteen he married an elderly widow - and it was not until 1710 that he was able to marry a younger

woman and have children of his own. In 1733 his first child, Gerd Heinrich, born

in 1711, inherited the family’s new farm in Oppenwehe, which had been given the number

53. For the next seven generations the family prospered there, although the number

of surviving children in each generation was small.

and it was not until 1710 that he was able to marry a younger

woman and have children of his own. In 1733 his first child, Gerd Heinrich, born

in 1711, inherited the family’s new farm in Oppenwehe, which had been given the number

53. For the next seven generations the family prospered there, although the number

of surviving children in each generation was small.

For American descendants of Oppenwehe 53, the most important event was the marriage

in 1852 of Heinrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, a non-

Heinrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1856

Emigrated in 1877 to Williamson County, Texas

Occupation: farmer

Married Caroline Charlotte Henriette Tiemann of Oppendorf in 1879

Children:

Henry Richard Priesmeyer, born in 1879 in Brenham, Texas

Fritz William Priesmeyer, born in 1881 in Williamson County, Texas

Emma Priesmeyer, born in 1883 in Austin County, Texas

Edward Henry Priesmeyer, born in 1885 in Williamson County, Texas

Wilhelmina Priesmeyer, born in 1888 in Williamson County, Texas

Ida Priesmeyer, born in 1892 in Williamson County, Texas

Lydia Priesmeyer, born in 1897 in Williamson County, Texas

Andrew Fred Priesmeyer, born in 1900 in Williamson County, Texas

Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Priesmeyer, born in 1859

Emigrated in 1880 to Williamson County, Texas

Occupation: farmer

Married Caroline Wilhelmine Henriette Henschen of Westrup in 1884

Children:

Adolph Carl Priesmeyer, born in 1888 in Austin County, Texas

Theodor H. Priesmeyer, born in 1893 in Austin County, Texas

Ida Priesmeyer, born in 1898 in Austin County, Texas

Caroline Henriette Engel Priesmeyer, born in 1863

Emigrated in about 1884 to Williamson County, Texas

Married Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Schwenker of Haldem in 1886

Carl Heinrich Priesmeyer, born in 1870, emigrated in 1888

Emigrated in 1888 to Williamson County, Texas

Occupation: farmer

Married Anna Louise Altus of Saxony in 1895

Children:

Helena Priesmeyer, born in 1896 in Williamson County, Texas

Frederick Priesmeyer, born in 1898 in Williamson County, Texas

Arthur John Priesmeyer, born in 1899 in Williamson County, Texas

As far as is known, they were the only offspring of Oppenwehe 53 to come to America. Their descendants now constitute a proud community based in Taylor, Texas, and they have published their own story on line.

Another child of this generation, Friedrich Heinrich Wilhelm, born in 1853, remained in Germany and settled in Brockum on farm number 18. Descendants of this line still live in the Brockum area and are actively involved in family history.

The Priesmeyers (Preasmeyer, Pruesmeyer) of Bonneberg:

Louisville, Kentucky

A branch unrelated to the Oppenwehe Priesmeyers is that of Louisville, Kentucky. This line originated in the village of Bonneberg, in Valdorf Parish, Westphalia. In the earliest records, the surname was actually Prüsner, but by about 1750 it had been altered to Prüssmeyer, evidently to distinguish the family from other Prüsner families in the parish.

In 1708, Johann Hermann Prüsner, heir to the family farm at Bonneberg 25, married Anne Hedwig Wittehus. Their great grandson, Johann Justus Friedrich Prüssmeyer, born in 1786, left Bonneberg and enlisted as a cannoneer in the Prussian Royal Artillery, stationed in the town of Minden. There he married Louise Margarethe Kohl of Petershagen, and they later settled in Petershagen. One of their sons, who wrote his surname as Priesmeyer or Preasmeyer, emigrated to America:

Carl August Priesmeyer, born in 1834 in Petershagen

Emigrated in 1860 to Louisville, Kentucky

Married Sophie Wilhelmine Caroline Marie Meyer of Petershagen in 1858

Children:

Charlotte Lina Sophie Priesmeyer, born in 1858 in Petershagen

Herman Albert Priesmeyer, born in 1861 in Louisville

Maria Lisette Friederike Auguste Priesmeyer, born in 1863 in Louisville

Heinrich Louis Priesmeyer, born in 1865 in Louisville

Wilhelmine Auguste Christine Priesmeyer, born in 1867 in Louisville

Louise Henriette Priesmeyer, born in 1869 in Louisville

Juliana Franziska Priesmeyer, born in 1871 in Louisville

Ella Priesmeyer, born in 1874 in Louisville

Alexander Priesmeyer, born in 1877 in Louisville

Anna Rebekka Priesmeyer, born in 1880 in Louisville

The Priesmeyers of Heddinghausen: Bond County, Illinois

Also not related to the Oppenwehe Priesmeyers is the lineage of Heddinghausen 9, in Holzhausen Parish, about twelve miles south of Oppenwehe. The antiquity of the farm suggests that it did not derive from Oppenwehe and that the similarity of the surnames is a coincidence. Even if there were a possibility of a connection before the beginning of written documents, the Heddinghausen line was itself cut off from its own Priesmeyer antecedents, so the descendants of the line are not genealogically Priesmeyers.

In 1730, the Priesmeyer heir of Heddinghausen 9 in that generation, Agnese Catharine, died young without producing a viable heir. Her widower, Jobst Hermann Klausing of Buer, Hannover, who had adopted the Priesmeyer surname at marriage, remarried and had a son, Caspar Heinrich, who eventually inherited the farm. A great grandson of Caspar Heinrich Priesmeyer came to America, evidently the only descendant of this line to emigrate:

Ernst Heinrich Priesmeyer, born in 1846 in Heddinghausen

Emigrated in 1882 and settled in Bond County, Illinois

Married Marie Louise Obermark of Buende in 1876

Children:

Louise Priesmeyer, born in 1877 in Heddinghausen

Johanne Friederike Elise Priesmeyer, born in 1879 in Heddinghausen

Henry Priesmeyer, born in 1882 in Illinois

Bernhard Priesmeyer, born in 1884 in Illinois

Emma Johanna Charlotta Priesmeyer, born in 1887 in Illinois

Wilhelmine Priesmeyer, born in 1889 in Illinois

Anna Priesmeyer, born in 1892 in Illinois

The Priesmeyers of Fischbeck: Morgan County, Missouri

A lineage that may have originated in Oppenwehe cannot now be connected, because it origins predated its first appearance in the written records, in Fischbeck, Hesse (in the modern state of Niedersachsen), about fifty miles southeast of Oppenwehe.

The earliest known ancestor of this line was Johann Cord Philip Priesmeyer, born in about 1707, who married Christine Sophie Peters in Fischbeck in about 1739. Their descendants lived for the following three generations in Fischbeck, and in about 1825 Heinrich Ernst Priesmeyer, born in 1803, left for Neersen, a village about fifteen miles to the south, near Bad Pyrmont in Niedersachsen. There he married Wilhelmine Dorothee Justine Jürgens in 1827, with whom he had eight children. After the death of his wife, in 1844, he married again, but in 1853, while still married, he had a son with unmarried Wilhelmine Caroline Catharine Wiedbrock.

In 1854, Heinrich and Wilhelmine, with their son, left Neersen for America and settled in Morgan County, Missouri. They evidently never married, probably because Heinrich could not conceal, upon investigation by their pastor, that he still had a wife in Germany:

Heinrich Ernst Priesmeyer, born in 1803 in Fischbeck

Emigrated in 1854 and settled in Morgan County, Missouri

Partner: Wilhelmine Caroline Catharine Wiedbrock (never married)

Children:

Heinrich Ernst Priesmeyer, born in 1853 in Neersen

Friedrich Priesmeyer, born in about 1856 in Morgan County, Missouri

Wilhelmine Caroline Margarethe Priesmeyer, born in about 1858 in Morgan County, Missouri

Ludwig Johann Priesmeyer, born in 1862 in Morgan County, Missouri

Gesche Margarethe Priesmeyer, born in 1864 in Morgan County, Missouri

Anna Catharina Priesmeyer, born in 1867 in Morgan County, Missouri

Louise Priesmeyer, born in 1870 in Morgan County, Missouri